| Journal of Food Bioactives, ISSN 2637-8752 print, 2637-8779 online |

| Journal website www.isnff-jfb.com |

Original Research

Volume 32, December 2025, pages 58-65

Proteo-stress induced by curcumin may confer resistance to the cytotoxicity of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

Erina Nakahataa, Kohta Ohnishia, Akira Murakamia, b, *

aDivision of Food Science and Biotechnology, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

bCurrent address, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, School of Human Science and Environment, University of Hyogo, Hyogo, Japan

*Corresponding author: Akira Murakami, Division of Food Science and Biotechnology, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan., E-mail: akira@shse.u-hyogo.ac.jp

DOI: 10.26599/JFB.2025.95032433

Received: October 21, 2025

Revised received & accepted: November 30, 2025

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Proteo-stress refers to cellular stress caused by disturbances in proteostasis, such as an increase in unfolded or aggregated proteins, whereas its roles in biofunctions of phytochemicals remain to be fully elucidated. Zerumbone has previously been shown to bind to cellular proteins in a non-specific manner to cause proteo-stress and activate the protein quality control (PQC) systems. In this study, we aimed to identify other phytochemicals that have properties similar to zerumbone. The formation of p62/SQSTM1 protein oligomers was evaluated in a screening assay. Among 28 nutrients and phytochemicals, curcumin markedly increased the formation of p62/SQSTM1 oligomers. Treatment with curcumin increased denatured proteins in an insoluble protein fraction. Moreover, two housekeeping proteins degraded or insolubilized by curcumin and zerumbone, and they significantly induced the formation of aggresomes. The amounts of curcumin-generated abnormal proteins increased in a time-dependent manner and thereafter decreased, suggesting the activation of adaptive mechanisms for proteostasis. In fact, both zerumbone and curcumin markedly upregulated the expressions of heat shock proteins. They markedly suppressed cell death induced by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Our results suggest that curcumin induces proteo-stress toward cellular proteins and the resultant activation of the PQC systems may protect the cell from proteo-toxic stimuli.

Keywords: Curcumin; Hormesis; Heat shock protein; Aggresome; Protein quality control.

| 1. Introduction | ▴Top |

Phytochemicals are plant secondary metabolites that exhibit versatile bioactivities in animal cells. Being basically non-nutritive and xenobiotic to animals, these chemicals stimulate adaptive and defensive machinery, including NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent induction of antioxidative and xenobiotics-metabolizing proteins and enzymes of the host (Qin and Hou, 2016). For example, sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate-type of phytochemical widely present in the Cruciferae plants, binds Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) for upregulating Nrf2-dependent expressions of heme oxygenase-1, NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase, glutathione-S-transferase, and so forth (Guerrero-Beltrán et al., 2012). Phytochemicals exhibit biological and physiological functions in animals through these enzymes that can mitigate oxidative and xenobiotic stresses. In addition, one can recognize that such responses are indispensable to detoxify and exclude phytochemicals that are incorporated into animal cells. This notion is supported by previous reports showing their toxicity and side-effects when administered at high doses (Inoue et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2010; Qiu et al., 2016).

There is ample evidence that some phytochemicals have specific binding proteins that trigger or mediate their mechanisms of action. For example, many studies have shown that flavonoids target the ATP-binding domain of several protein kinases (Jung et al., 2016). These findings raise a big question as to why or how animals have developed such specific binding proteins for the plant secondary metabolites. In other words, one may be wondering if the presence of specific binding proteins represents adaptive responses during evolutionary processes or simply coincidence. In contrast to synthetic drugs, phytochemicals have simple chemical structures with smaller molecular weights. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that phytochemicals exhibit much more off-target effects compared with drugs. However, to date, there is little information about their non-specific bindings to biological proteins, and it is still uncertain whether such putative bindings have any roles in their physiological functions or side-effects. We previously uncovered that zerumbone, an electrophilic sesquiterpene in Zingiber zerumbet Smith, non-specifically bound cellular proteins for activating protein control (PQC) systems, such as the upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSPs), the proteasome, and autophagy (Ohnishi et al., 2013a, 2013b). This agent randomly targets the functional groups of biological proteins, including the cysteine thiol groups. It should be indicated that many recent studies have shown that proper and continuous activation of PQC systems has a great impact on our health and disease prevention (Rogers et al., 2015; Dokladny et al., 2015). Given these recent essential findings, we previously examined whether the non-specific protein interactions of zerumbone contribute to its anti-inflammatory functions because suppression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-1β partially depended on non-specific binding mode (Igarashi et al., 2016).

Although hydrophobic or electrophilic phytochemicals, including curcumin, ursolic acid, and phenethyl isothiocyanate, significantly upregulated HSP70 mRNA in hepatocytes (Ohnishi et al., 2013a), their properties for inducing proteo-stress remain to be demonstrated. Proteo-stress refers to cellular stress caused by disturbances in proteostasis, such as an increase in unfolded or aggregated proteins. Therefore, in this study, we attempted to identify the phytochemicals that induce proteo-stress in cultured cells, and the formation of p62/SQSTM1 protein oligomers (Leu et al., 2009) was employed to screen a total of 28 phytochemicals and nutrients.

| 2. Materials and methods | ▴Top |

2.1. Cell culture

Hepa1c1c7 mouse hepatocytes were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

2.2. Materials

DMEM was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and FBS from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY). Antibodies (Abs) were obtained from the following sources: mouse anti-ubiquitin (Ub), rabbit anti-p62/SQSTM1, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); mouse anti-HSP90β Ab were from Enzo Biochem Inc. (New York, NY); mouse anti-α-tubulin Ab was from EMD Bioscience (La Jolla, CA); goat anti-β-actin Ab and goat anti-lamin B Abs were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); goat anti-GAPDH, and HRP-conjugated anti-goat and anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Dako (Tokyo, Japan). Zerumbone was purified (>95%) as previously reported (Murakami et al., 1999). All other chemicals were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co. (Osaka, Japan), unless otherwise specified.

2.3. Western blot

Hepa1c1c7 cells (2 × 105 cells/1 mL/24-well plate) were treated with the sample or vehicle (0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO, v/v) for specified times and then lysed in BioPlex cell lysis buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Denatured proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, then transferred onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After blocking with 2% Block Ace at room temperature for 1 hour, each membrane was treated with a specific primary Ab (1:2,000 dilution), followed by the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary Ab (1:2,000). The blots were developed using ECL western blot detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.4. Fractionation of the cell lysates

The extraction of soluble cell lysates was performed using a ReadyPrep™ Protein Extraction Kit (Soluble/Insoluble) (Bio-Rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s protocol with some modifications. Hepa1c1c7 cells (2 × 105 cells/1 mL/24-well plate) were treated with the sample or vehicle (0.5% DMSO, v/v) for 12 or 18 h, then lysed with 30 μl lysis buffer from the kit followed by sonication by Bioruptor at level 3 (Cosmo Bio, USA) for 1 min. After centrifugation (16,000 × g, 30 min), the supernatant thus obtained was designed as a soluble fraction. On the other hand, the pellets were extracted with 30 μl lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium metavanadate [V]) and then sonicated for 2 min. After centrifugation (16,000 g, 5 min), the supernatant was designed as an insoluble fraction.

2.5. Detection of the intracellular aggresomes

Fluorescent staining of cellular aggresomes was performed using a ProteoStat Aggresome Detection Kit (Enzo Life Science, New York, NY), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hepa1c1c7 cells were (4 × 104 cells/200 μL/96-well plate) treated with the sample or vehicle (0.5% DMSO, v/v) for 12 h. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 on ice. The cells were incubated with Proteostat Aggresome Detection Reagent (1:4,000 dilution) and Hoechst 33342 (1:4,000 dilution). Images of cellular immunofluorescence were acquired using an UFX-35A fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo) (original magnification: ×400).

2.6. The quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Hepa1c1c7 cells (1.0 × 106 cells/1 mL/24-well plate) were treated with the sample or vehicle (0.5%, v/v) for 12 h. Total RNA extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Velno, Netherlands). Total RNA concentrations were calculated by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. cDNA was synthesized using total RNA (1 µg) with 25 mM MgCl2 (4 µL), RNA PCR buffer (2 µL), 2 mM dNTP (2 µL), 40 U/µL RNase inhibitor (0.5 µL), 5 U/µL AMV RTase (1 µL) and 1 g/L oligo-dT adaptor primer (1 µL) by RT reaction. RT reaction was p by using a Programable Thermal Controller PTC-100 (MJ Research, St. Bruno, Canada). The conditions of cDNA amplification were as follows: 30 °C for 10 min, 55 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 5 min, and 4 °C for 15 min. Five µl cDNA was mixed with a sense- and antisense-primer (10 pmol, 4.5 µL), Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (25 µL), and ultrapure water (11 µL) for real-time PCR. Thermal cycling was performed using a 7300 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR was performed as follows: 50 °C 2 min and 95 °C 2 min for 1 cycle, and 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 30 sec for 99 cycles. The relative mRNA levels were estimated using the ΔΔCt method. Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase was used as an internal standard. The sequences of the primers, which were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), are shown in Table 1.

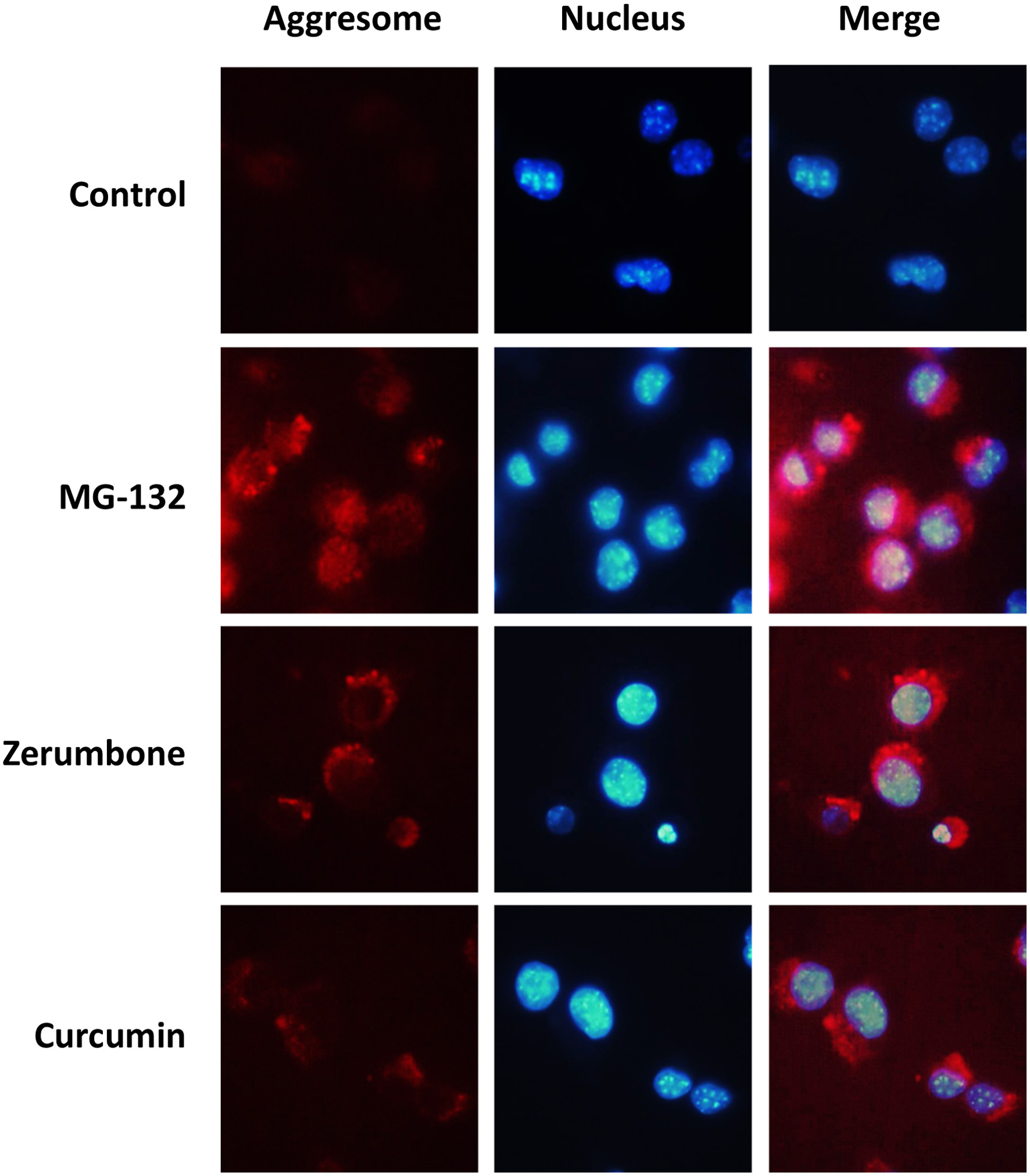

Click to view | Table 1. The primers used for real-time RT-PCR |

2.7. Cytotoxicity test

Hepa1c1c7 cells (4 × 104 cells/200 μL/96-well plate) were pre-treated with vehicle (0.5% DMSO, v/v), zerumbone, or curcumin (1–200 μM each) for 6 h. After washing with PBS, they were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 18 hours, followed by exposure to 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE, 0 or 200 μM) for 0, 80 or 100 min. Cell viability was determined using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (WST-8, Dojindo Molecular Technology, Kumamoto) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were incubated in DMEM containing 5% WST at 37 °C for 45 min, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least 3 times and values are shown as the means ± SD, where applicable. Statistically significant differences between the groups in each assay were determined using Dunnett’s test and Student’s t-test (two-sided). P < 0.05 was evaluated as statistically significant.

| 3. Results | ▴Top |

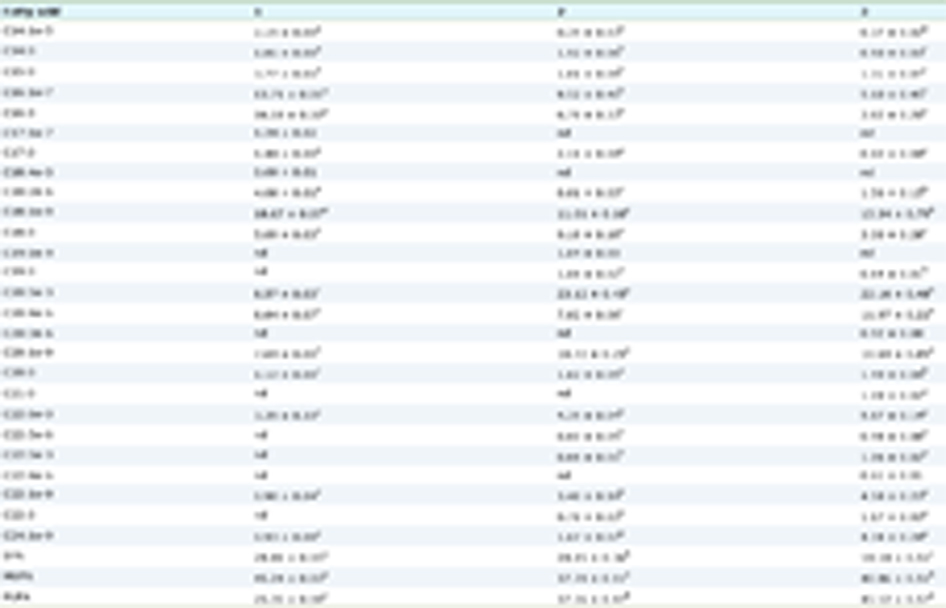

3.1. Screening of phytochemicals for their proteo-stress-inducing activities

To examine whether phytochemicals induce proteo-stress, we conducted western blotting analysis for detecting p62/SQSTM1 oligomers (Leu et al., 2009), which consist of ubiquitinated, denatured proteins, and are degraded via autophagy (Pankiv et al., 2007). The effects of several groups of nutrients were also tested since they are mostly inactive for upregulating HSP70 mRNA (Ohnishi et al., 2013a). Hepa1c1c7 mouse hepatoma cells were treated with each test agent at the maximum, nonlethal concentrations, which were determined in preliminary experiments (data not shown), for 12 h. Interestingly, the upper ladder bands representing the p62/SQSTM1 oligomers were markedly detected in both curcumin (50 μM, lane 5)- and zerumbone (100 μM, lane 7)-treated cells, and non-bound p62 protein concomitantly decreased (Figure 1a, upper panel). In contrast, 16 nutrients, consisting of saccharides, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, were largely inactive and several nutrients increased non-bound p62 (Figure. 1a, lower panel). Both zerumbone (25–100 μM) and curcumin (10–100 μM) markedly decreased the expression levels of non-bound p62 or increased p62/SQSTM1 oligomers (Figure 1b). In addition, both zerumbone- and curcumin-induced p62/SQSTM1 oligomers reached a maximum at 12 h and 6 hours, respectively, during a 24-h incubation (Figure 1c).

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Curcumin (lane 5) and zerumbone (lane 7) markedly formed the p62 conjugated proteins. Hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with vehicle (0.5% DMSO) or phytochemicals for 12 h and then lysed for western blot analysis. β-actin was used as the internal standard. Lane 1, control; Lane 2, quercetin (100 μM); Lane 3, ellagic acid (50 μM); Lane 4, (–)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (10 μM); Lane 5, curcumin (50 μM); Lane 6, resveratrol; Lane 7, zerumbone (100 μM); Lane 8, α-humulene; Lane 9, ursolic acid (5 μM); Lane 10, phenethyl isothiocyanate (10 μM); Lane 11, sulforaphane (25 μM); Lane 12, diallyl trisulfide c; Lane 13, benzoic acid (100 μM); Lane 14, fructose (5 mM): Lane 15, glucose (5 mM); Lane 16, L-arginine (5 mM); Lane 17, L-asparagine (1 mM); Lane 18, vitamin A (50 μM); Lane 19, vitamin D (50 μM); Lane 20, vitamin E (250 μM); Lane 21, vitamin K (500 μM); Lane 22, vitamin B1 (10 mM); Lane 23, vitamin B3 (niacin, 5 mM); Lane 24, vitamin B6 (10 mM); Lane 25, vitamin B12 (100 μM); Lane 26, vitamin C (100 μM); Lane 27, vitamin M (folic acid, 500 μM); Lane 28, MnSO4 (25 μM); Lane 29, ZnCl2 (50 μM). Effects of concentrations and incubation times of zerumbone, curcumin and resveratrol on p62 conjugation. (b) Hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with zerumbone (25, 50, 100 μM), curcumin (10, 25, 50, 100 μM) or vehicle for 12 h. (c) Cells were treated with zerumbone, curcumin, resveratrol (50 μM) or vehicle for 6, 12, 18 h. Expression levels of p62 protein were analyzed by western blotting, and β-actin was used as the internal standard. CUR, curcumin; ZER, zerumbone. |

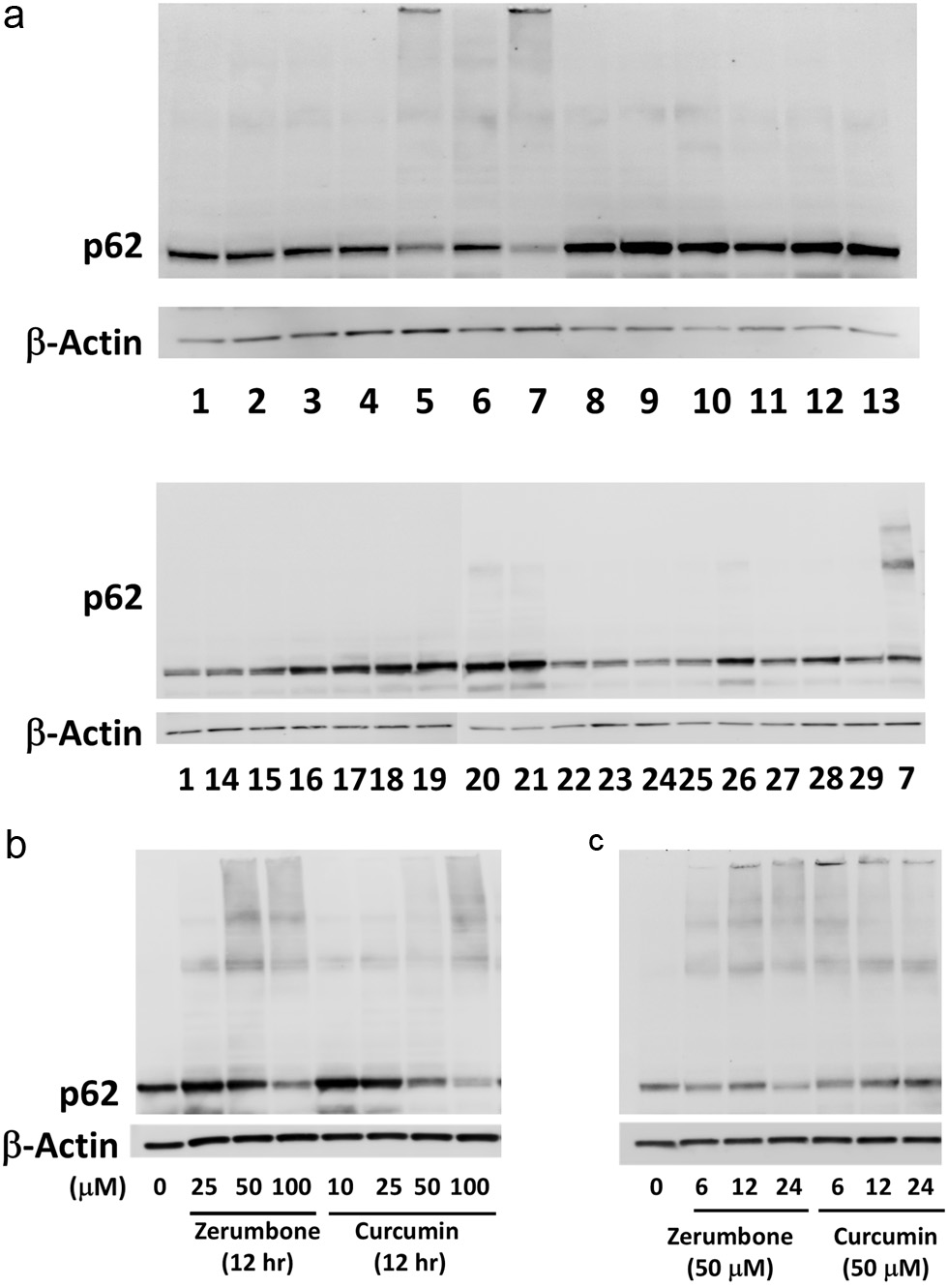

3.2. Curcumin insolubilized housekeeping proteins

Upon denaturing, the hydrophobic region of a protein is extremely exposed and associated with such regions of other proteins to form aggregates. Hence, denatured proteins and aggregates generally have poor water solubility. Thus, the distribution of housekeeping proteins in the insoluble and soluble fractions of cell lysates was determined. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and lamin B were used to validate the fractionations of soluble and insoluble proteins, respectively. In addition, because denatured proteins are ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (CHIP) (Murata et al., 2001), the status of these proteins and p62 were also investigated. Cellular proteins were lysed with two types of buffers with different detergence’s and separated into the soluble and insoluble fractions after treatment with the vehicle, zerumbone (100 μM) or curcumin (50 μM) for 12 h. A heat shock (45 °C for 120 min) was employed as a positive control. It is noted that p62/SQSTM1 oligomers and ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction increased by heat shock, and similar results were observed for both zerumbone and curcumin, as compared with control (Figure 2). Interestingly, GAPDH was hardly detectable when cells were treated with heat shock, zerumbone, and curcumin, and were detected in the insoluble fraction in the case of zerumbone. Moreover, heat shock treatment led to a dramatic insolubilization of α-tubulin, while both zerumbone and curcumin partially insolubilized it. HSP90β, the major molecular chaperone, was found to be insolubilized only by heat shock.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Insolubilization of housekeeping proteins by zerumbone and curcumin. Cells treated with zerumbone (100 μM), curcumin (50 μM) for 12 h were lysed, then fractionated into soluble and insoluble proteins using a ReadyPrep™ Protein Extraction Kit for western blot analysis. CTL, control; CUR, curcumin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HS, heat shock; I, insoluble; S, soluble; ZER, zerumbone. |

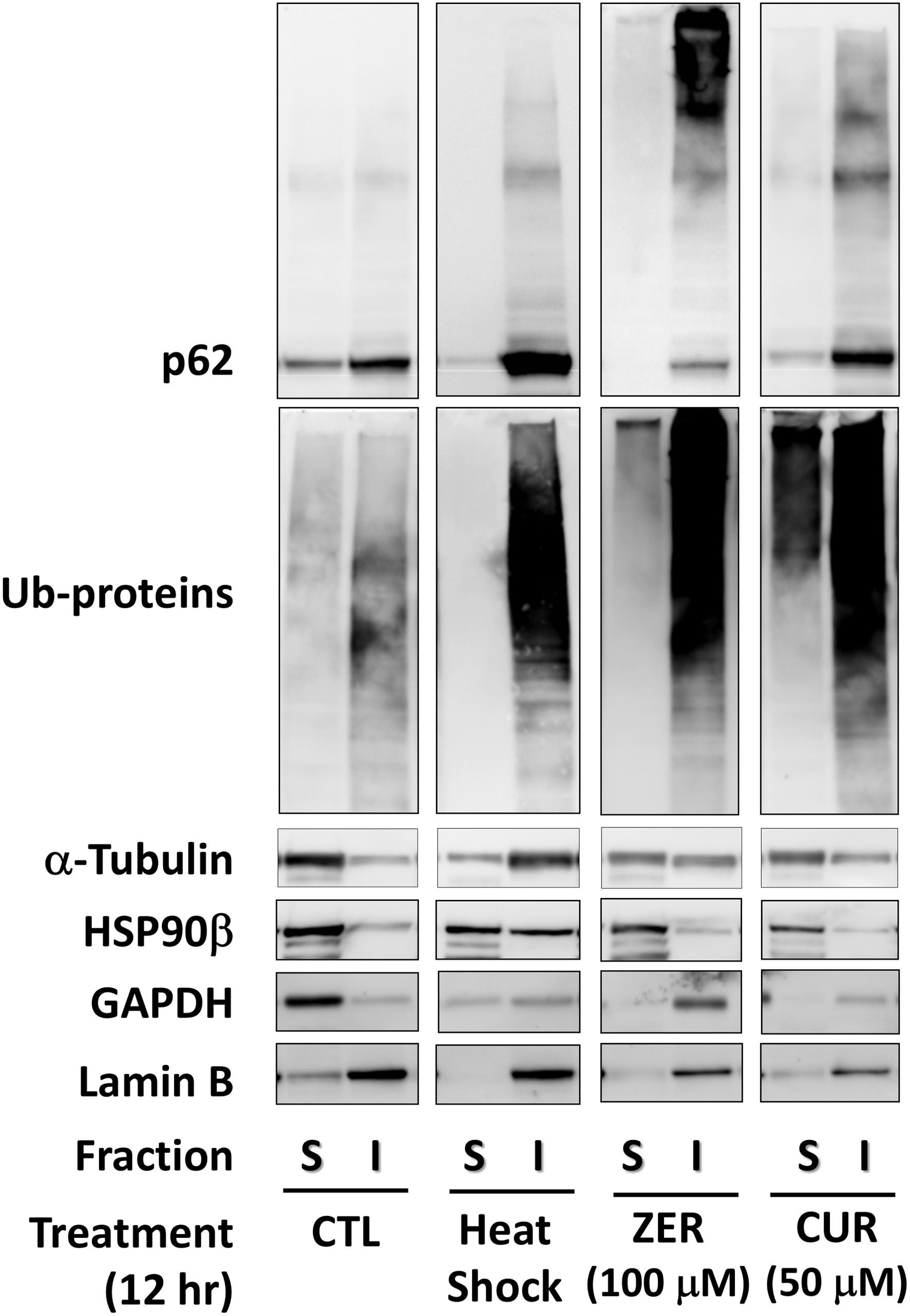

3.3. Curcumin-induced aggregation of cellular proteins

In mammalian cells, aggregated proteins may be concentrated by microtubule-dependent retrograde transport to the perinuclear sites of aggregate deposition, referred as the aggresomes (Kopito, 2000). The aggresomes are inclusion bodies that are formed when the ubiquitin-proteasome machinery is overwhelmed with aggregation-prone proteins (Amijee et al., 2009). To confirm the aggresome formation, cells treated with the vehicle or test compounds were stained with a molecular rotor dye for the aggresomes (Haidekker and Theodorakis, 2010). As a result, treatment with MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor used as a positive control, remarkably increased the levels of cellular aggresomes (Figure 3). Similarly, both zerumbone (10 μM) and curcumin (5 μM) induced notable formations of the aggresomes.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Detection of cellular aggresomes induced by phytochemicals. Hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with zerumbone (10 μM), curcumin (5 μM), or MG-132 (10 μM) for 12 h, and then cellular aggresomes and nucleus were stained using a ProteoStat Aggresome Detection Reagent and Hoechst 33342, respectively. CTL, control; CUR, curcumin; ZER, zerumbone. |

3.4. Curcumin may activate PQC systems for adaptation

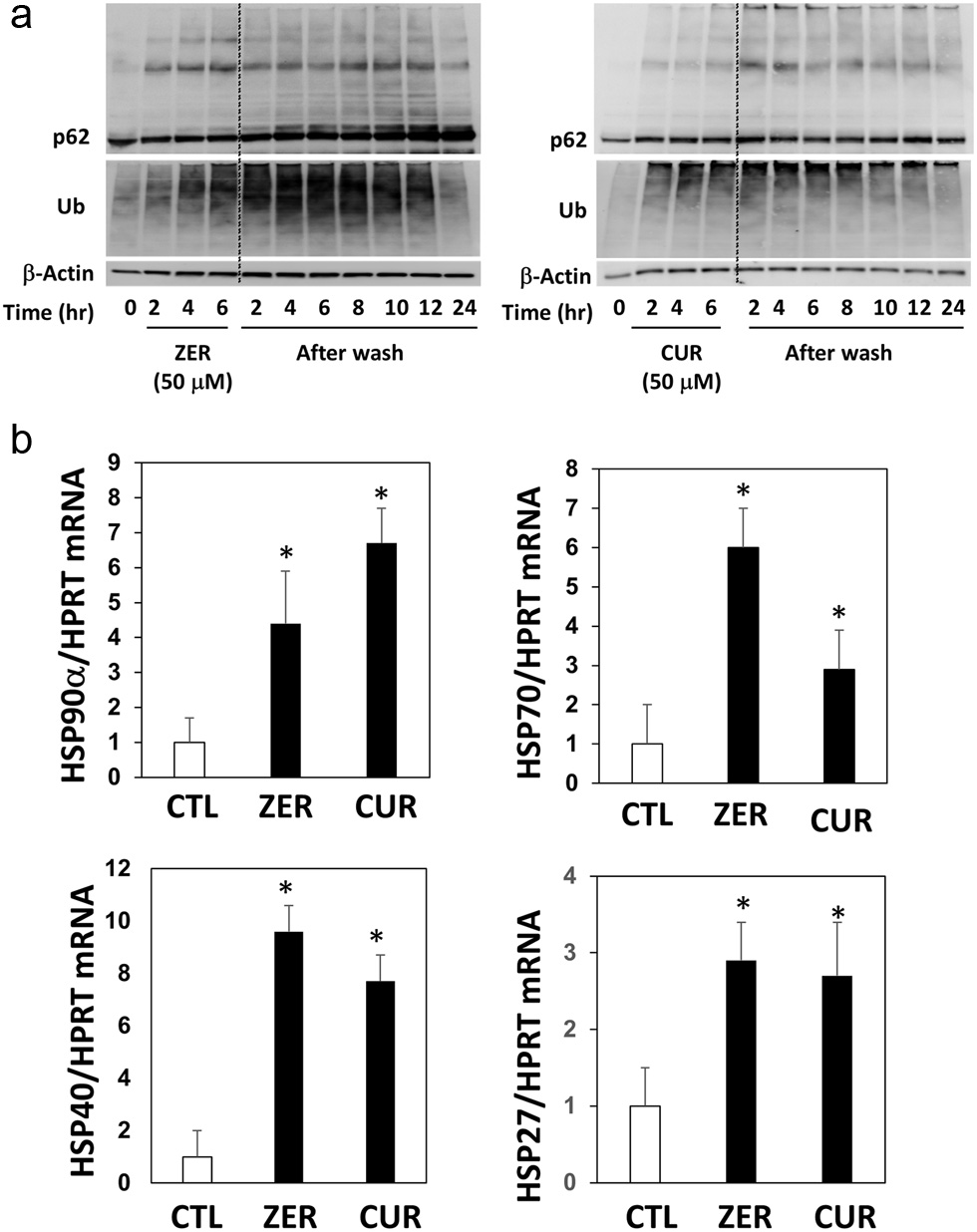

Upon proteo-stress, cells may activate PQC systems, such as the induction of HSPs and the execution of the proteasome and autophagy for proteostasis (Balch et al., 2008). Thus, there is a possibility that the formation of abnormal proteins induced by curcumin is reversible. To ascertain this hypothesis, we incubated the cells with vehicle, zerumbone or curcumin for 6 h, then they were washed with PBS to remove these phytochemicals in the media, followed by another incubation for 24 h. As a result, both p62/SQSTM1 oligomers and ubiquitinated proteins dramatically increased before washing the cells and then significantly decreased 24 h after washing (Figure 4a). Interestingly, the expression levels of non-bound p62/SQSTM1 were higher in the cells treated with those agents compared with those in the non-treated cells. In addition, qRT-PCR analyses revealed that both zerumbone and curcumin markedly upregulated the mRNA expression of several types of HSPs (Figure 4b).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Time course of p62 conjugation and protein ubiquitination by zerumbone and curcumin after washing cells. Hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with (a) zerumbone, (b) curcumin (50 μM each), or vehicle control for 6 hours, then cultured in DMEM without FBS for another 2–24 h. The expression levels of p62 and ubiquitin were analyzed by western blotting. CUR, curcumin, zerumbone. (b) Hepa1c1c7 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and treated with the sample or vehicle (0.5%, v/v) for 12 h. cDNA was synthesized using total RNA (1 µg) and real-time PCR was performed as follows: 50 °C 2 min and 95 °C 2 min for 1 cycle, and 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 30 sec for 99 cycles. The relative mRNA levels were estimated using the ΔΔCt method. HPRT was used as an internal standard. *P < 0.05 vs. CTL by Student’s t-test. CTL, control. |

3.5. Curcumin conferred resistance to HNE-induced cell death

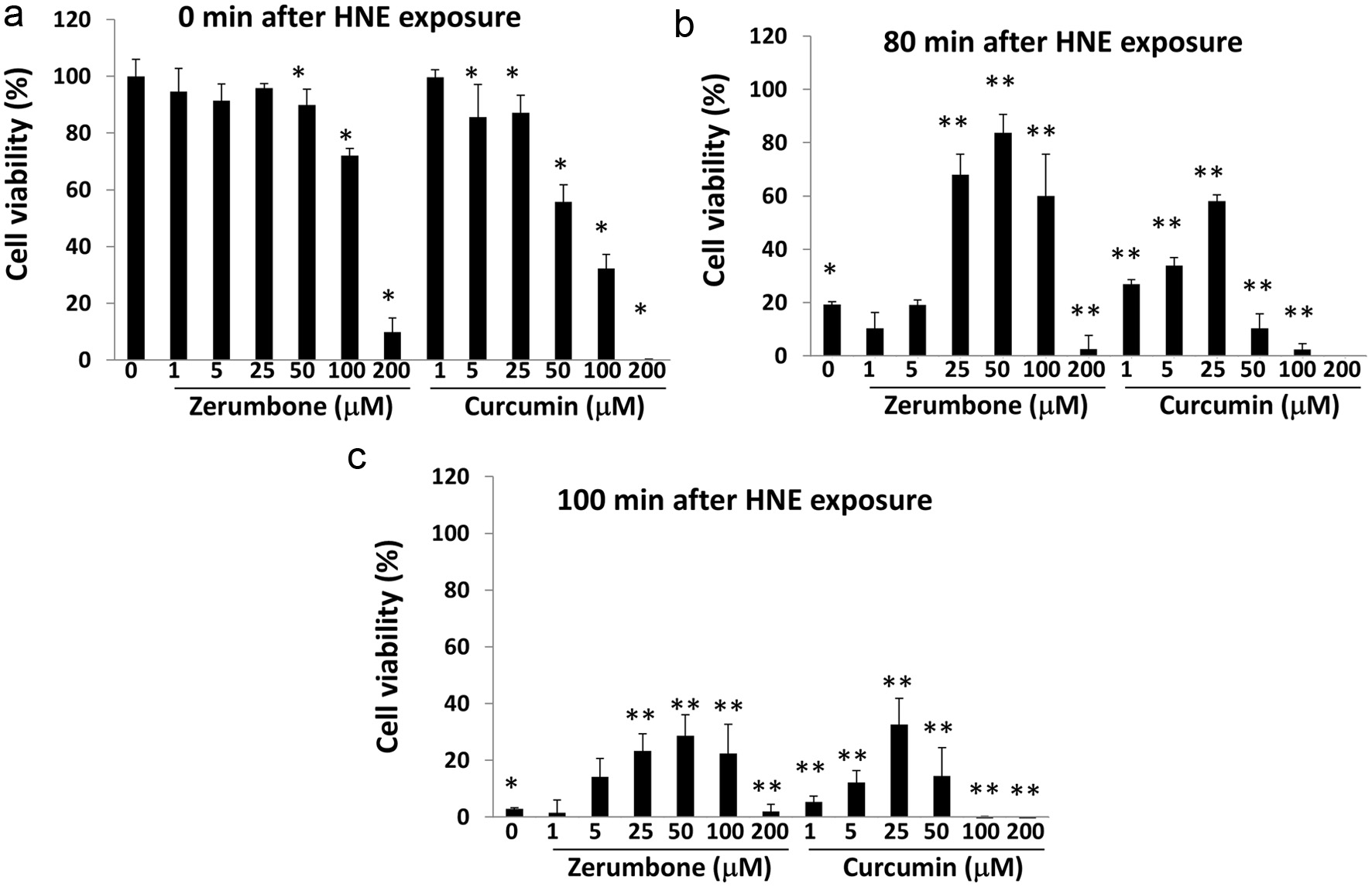

Although excessive stress apparently induces toxicity in an organism, moderate one may potentiate adaptation capability and thus confer resistance to additional stresses. The phenomenon that mild stress may confer some beneficial effect is called ‘hormesis’ (Calabrese, 2004). To demonstrate the hormetic effects of zerumbone and curcumin, their protective effects toward the cytotoxicity of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), a major degradation product of lipid peroxides being known to intensively modify cellular proteins (Codreanu et al, 2009), were determined. After being treated with vehicle, zerumbone, or curcumin (1–200 μM each) for 6 h, the cells were washed with PBS to remove the agents and then incubated for 18 h for cell viability measurement. Those phytochemicals exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity at higher concentrations (Figure 5a), whereas treatment with HNE for 80 min dramatically decreased cell viability down to 20% in vehicle pre-treated cells (Figure 5b). Interestingly, pre-treatment with zerumbone (25–100 μM) notably protected cells from HNE toxicity, which was consistent with previous work (Ohnishi et al., 2013b). Also, treatment with curcumin (1–25 μM) conferred a resistant phenotype to cytotoxicity by HNE. Importantly, pretreatments with those agents at higher concentrations (200 μM for zerumbone and 50–200 μM for curcumin) led to substantial cytotoxicity (Figure 5b, c). Similar inverted U-shape responses were observed for the cells treated with HNE for 100 min (Figure 5c).

Click for large image | Figure 5. Zerumbone and curcumin conferred resistance to HNE-induced cell death. Hepa1c1c7 cells were pre-treated with each phytochemical (0–200 μM each) for 6 h. After washing, they were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS for another 18 hours, followed by exposure to HNE (0, 200 μM) for 0 (a), 80 (b), or 100 (c) min. Then, cell viability was determined using a WST-8 kit. Panel A, *P < 0.05 vs. CTL, Panel B, *P < 0.05 vs. CTL (0 min), **P < 0.05 vs. CTL (80 min). Panel C, *P < 0.05 vs. CTL (0 min), **P < 0.05 vs. CTL (100 min). CTL, control. |

| 4. Discussion | ▴Top |

In the present study, a total of 28 phytochemicals and nutrients were screened for their effects on the formation of p62/SQSTM1 protein oligomers, which is associated with proteo-stress. As a result, curcumin, one of the extensively studied phytochemicals for its diverse bioactivities (Ghosh et al., 2015; Park et al., 2013), was identified to be an effective agent (Figure 1a). Also, curcumin markedly increased the amounts of insolubilized house-keeping proteins and both p62/SQSTM1 oligomers and ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 2) and induced the formation of cellular aggresomes (Figure 3). These findings are consistent with our previous report showing that curcumin possesses the biochemical properties that potentially disrupt cellular proteostasis in Huh7 hepatocytes (Valentine et al., 2019). It is interesting to point out that some stimuli denaturing cellular proteins upregulated various types of HSPs for proteostasis (Balch et al., 2008). Importantly, our previous study found that curcumin was the most potent HSP70 inducer among the tested phytochemicals (Ohnishi et al., 2013a), which was supported in the present study (Figure 4b). It, however, is still uncertain whether curcumin directly bound cellular proteins in a non-specific manner or its degraded compound(s) have any significant roles in proteo-stress functions. On one hand, it is worth noting that curcumin, but not other compounds tested in the present study, has an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group, which has an electrophilic property and is also present in zerumbone. This raises the possibility that curcumin binds nucleophilic amino acid residues of cellular proteins via Michael reaction, which was indeed demonstrated by previous studies (Gradisar et al., 2007; Jung et al., 2007). On the other hand, it is well known that curcumin is chemically and biologically unstable to generate several degradation products and metabolites, some of which are electrophilic (Esatbeyoglu et al., 2015). Therefore, further studies focusing on the roles of those degraded compounds are necessary to be conducted.

Meanwhile, only zerumbone and curcumin were found to markedly induce p62/SQSTM1 oligomers in our screening tests (Figure 1). However, it has been reported that phenethyl isothiocyanate, which was inactive in our present test, promoted the formation of a cellular aggresome-like structure and induced protein ubiquitination (Mi et al., 2009). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the induction of proteo-stress by phenethyl isothiocyanate and other inactive phytochemicals in this study could be detected under harsher conditions and/or in different cell types. In any case, the screening tests revealed that none of the tested nutrients induced the formation of p62/SQSTM1 oligomers. These results have some associations with those in our previous study showing that all 16 tested nutrients, except for vitamin A and zinc chloride, did not upregulate HSP70 expression (Ohnishi et al., 2013a). Taken together, the aforementioned data support our hypothesis that proteo-stress can be preferentially induced by phytochemicals, but not by nutrients, and thus they are described as unique chemicals that have a marked potential to activate the defense systems of animal cells.

In this study, the expression levels of non-bound p62/SQSTM1 changed in a condition-dependent manner. For example, treatments with zerumbone and curcumin for 12 h apparently decreased non-bound p62/SQSTM1 (Figure 1a). This is presumably due to its oligomerization for be recruited to the autophagosome (Komatsu et al., 2012). In contrast, non-bound p62/SQSTM1 increased after treatment with zerumbone and curcumin for 24 h compared with the non-treated control (Figure 4a). Jain et al. reported that p62/SQSTM1 expression is regulated by the transcription factor Nrf2 (Jain et al., 2010), whereas these phytochemicals have been shown to activate Nrf2 (Shin et al., 2011, Yang et al., 2009), suggesting that they upregulate p62 expression through Nrf2 activation. The above findings support the notion that mild proteo-stress activates the PQC systems to prepare for and overcome additional stresses for adaptation. On the other hand, it is notable that the p62/SQSTM1 oligomers and ubiquitinated proteins increased by zerumbone and curcumin dramatically decreased 24 h after the cells were washed to remove those phytochemicals in the culture media (Figure 4a). Upregulations of several HSP isoforms (Figure 4b) may partially account for the decrease in abnormal proteins, which may also have been degraded in the proteasome or autophagy for proteostasis.

In principle, a severe stress critically damages biomolecules (e.g., proteins, DNA, cell membrane) for cell death, while a mild stress is potentially capable of activating self-defense systems. It is conceivable that mild proteo-stress promotes the PQC systems, such as the expression of chaperone proteins and induction of proteasome systems and autophagy. We previously reported that zerumbone induces cellular proteo-stress, activating the Ub-proteasome system and autophagy (Ohnishi et al., 2013b). Interestingly, curcumin (1–25 μM) exhibited pronounced cytoprotective activity against HNE-induced toxicity, whereas those at higher concentrations (50–200 μM) were evidently toxic (Figure 5). The graphs of their cytoprotective effects represent the inverse U-shaped curve, which is consistent with the principle of hormesis (Calabrese, 2004). Again, these observations are in line with the notion that the beneficial and harmful effects of phytochemicals depend on the experimental conditions, such as the concentration of the agents. To support this notion, high-dose green tea polyphenols were reported to induce nephrotoxicity in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis mice, while a moderate dose was beneficial (Inoue et al., 2011, 2013). HNE, a major degradation product of lipid peroxides, binds cellular proteins via the Michael reaction, and thereby exhibits cytotoxicity (Codreanu et al., 2009). Hence, it is presumed that the cytoprotective effects of curcumin on HNE toxicity may be derived from the activation of PQC systems.

Although curcumin has been shown to exhibit diverse bioactivities, its molecular target and precise mechanisms of action remain to be fully demonstrated. Gupta et al. have pointed out that curcumin has multiple targets, which were identified in molecular interaction studies (Gupta et al., 2011) and modulates diverse signal transduction pathways, which are associated with anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory functions (Kunnumakkara et al., 2008, Martínez-Palacián et al., 2013). Meanwhile, many studies have revealed that activation of PQC systems profoundly contributes to the prevention of many diseases and longevity (Wilson et al., 2014, Markaki and Tavernarakis, 2013). For example, heat shock factor 1, a master transcription factor in the PQC system, plays several major roles in anti-inflammatory responses through the upregulation of HSPs (Tanaka et al., 2014) and the promotion of autophagy (Dokladny et al., 2015). It is of great importance to indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of zerumbone were partially dependent upon its unique property relating to proteo-stress and resultant PQC activation (Igarashi et al., 2016). Thus, studies on role of proteo-stress by curcumin in its anti-inflammatory functions are warranted.

| 5. Conclusions | ▴Top |

The present findings showed that curcumin exhibited a proteo-stress-inducing property in Hepa1c1c7 mouse hepatocytes. Although this agent has been recognized as one of the most promising phytochemicals with few side-effects, we uncovered a novel molecular aspect that may potentiate PQC systems that are known to have positive associations with the prevention of various diseases and longevity. Thus, proteo-stress induced by curcumin may contribute to its mechanisms of action, while the issue of the active principle, i.e., curcumin itself or its degraded product(s), should be addressed in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 26450156 and No. 19K05913 to A.M.), Scientific Research (A) (No. 17H00818 to A.M.), Urakami Foundation for Food and Food Culture Promotion (to A.M.), and a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (No. 22.3355 to K.O.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (A.M.) upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Author contributions

All authors designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. E.N. and K.O. performed the experiments. A.M. administered this research.

| References | ▴Top |