| Journal of Food Bioactives, ISSN 2637-8752 print, 2637-8779 online |

| Journal website www.isnff-jfb.com |

Original Research

Volume 32, December 2025, pages 51-57

Mikan-fermented tea enhanced hesperidin bioavailability: In vivo pharmacokinetic and in vitro Caco-2 Cell

Arata Bannoa, Yutaka Yoshinob, Yuji Miyatac, Hisayuki Nakayamac, Toshiro Matsuia, *

aFaculty of Agriculture, Graduated School of Kyushu University, 744 Motooka, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan

bSandai. Co., Ltd, 858-6 Sudanoki-machi, Ohmura, Nagasaki 856-0047, Japan

cIndustrial Technology Center of Nagasaki, 2-1303-8 Ikeda, Ohmura, Nagasaki 856-0026, Japan

*Corresponding author: Toshiro Matsui, Faculty of Agriculture, Graduate School of Kyushu University, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan. Tel/Fax: +81-928024752/+81-928024752; E-mail: tmatsui@agr.kyushu-u.ac.jp

DOI: 10.26599/JFB.2025.95032432

Received: November 11, 2025

Revised received & accepted: November 29, 2025

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Hesperidin, a flavanone glycoside abundantly found in citrus fruits, has been reported to exert a wide range of biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-adipogenic, anti-allergic, anti-carcinogenic, antiviral, insulin-sensitizing, hypolipidemic, neuroprotective, and vasoprotective effects. However, bioactive efficacy is limited by its poor water solubility, low absorption, and restricted bioavailability. In this study, we hypothesized that Mikan-fermented tea could enhance the bioavailability of hesperidin by increasing its solubility. To test this, we evaluated the pharmacokinetics of hesperidin in Sprague-Dawley rats following oral administration of the Mikan-fermented tea. We also investigated the mechanisms underlying its enhanced transport of hesperidin using Caco-2 cell monolayers. Our in vivo results demonstrated that oral administration of Mikan-fermented tea significantly increased the Cmax (∼3.6-fold) and AUC0–24 (∼2.4-fold) of hesperidin (measured as hesperetin aglycone) compared to hesperidin alone. In vitro transport studies revealed that Mikan-fermented tea promoted basolateral transport and reduced intracellular accumulation of hydrophobic hesperidin in Caco-2 cells, strongly indicating improved intestinal absorption and systemic bioavailability.

Keywords: Hesperidin; Mikan-fermented tea; Bioavailability; Food matrix effect; Caco-2

| 1. Introduction | ▴Top |

Flavanones represent a relatively small subgroup of the ubiquitous plant flavonoids and exist in both glycoside and aglycone forms. Most extensively studied aglycones include eriodictyol, hesperetin, isosakuranetin, and naringenin, while prominent glycosides include hesperidin and naringin. Hesperidin is a flavanone glycoside composed of hesperetin (aglycone) and rutinose (a disaccharide of glucose and rhamnose) (Garg et al., 2001). It has been reported to exhibit various physiological effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-adipogenic, anti-allergic, anti-carcinogenic, antiviral, insulin-sensitizing, hypolipidemic, neuroprotective, and vasoprotective properties (Brglez Mojzer et al., 2016, Huang et al., 2010, Roohbakhsh et al., 2015). However, hesperidin exhibits negligible water solubility (Grohmann et al., 2000), which greatly limits its absorption and bioavailability, ultimately impairing its physiological effectiveness.

To address this issue, a novel approach involving the development of Mikan-fermented tea has been explored. This tea is produced by fermenting immature mandarin oranges–rich in hesperidin– with third-harvest green tea leaves (Miyata et al., 2009). The fermentation process is believed to improve the water solubility of hesperidin (Nakayama et al., 2014). The enhancement is thought to result from interactions between hesperidin and various water-soluble polyphenols found in tea leaves, such as catechins and theaflavins. These compounds may disrupt the self-association of hesperidin molecules through hydrophobic interactions, thereby increasing its solubility. Mikan-fermented tea has also been reported to exhibit lipid metabolism-improving and anti-obesity effects in rats (Nakayama et al., 2015), supporting its potential as a functional food. Despite this, there is a lack of quantitative data on hesperidin absorption from Mikan-fermented tea. Unlike conventional pharmaceutical strategies that rely on synthetic surfactants or complex solid dispersions to enhance bioavailability, which are often limited by cost and safety concerns (Singh et al., 2023), our approach utilizes the natural food matrix of Mikan-fermented tea. This offers a distinct translational advantage for developing safe and cost-effective functional foods that do not contain artificial additives.

In the present study, we investigated the absorption profile of hesperidin in rats after oral administration of Mikan-fermented tea to evaluate its bioavailability. Furthermore, we explored the underlying mechanisms by comparing hesperidin uptake in Caco-2 cells with and without the Mikan-fermented tea matrix. Our findings are expected to contribute to the development of more effective dietary strategies for hesperidin intake and to support the creation of functional food products that leverage its physiological benefits.

| 2. Materials and methods | ▴Top |

2.1. Materials

Mikan-fermented tea was prepared according to our previously reported method (Nakayama et al., 2015). The compositional profile of this matrix, including synephrine, narirutin, tea catechins, and polymerized polyphenols (e.g., theasinensins), has been characterized previously (Nakayama et al., 2014). In this study, the content of the key bioactive marker, hesperidin, was quantified at 14 mg/g to ensure quality and dose standardization. This standardized extract was used for both animal experiments and in vitro transport studies. Hesperidin was obtained from Funakoshi Co. (Tokyo, Japan), hesperetin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and taxifolin from TCI Fine Chemicals (Tokyo, Japan). Sulfatase type H-1 (EC 3.1.6.1, from Helix pomatia) and β-glucuronidase type B-1 (EC 3.2.1.31, from bovine liver) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Animal experiments

Eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from KBT Oriental Co., Ltd. (Saga, Japan). The rats were individually housed under controlled environmental conditions (21 ± 1 °C, 55.5 ± 5 % humidity) with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on 08:30 to 20:30. They were fed a standard laboratory diet (CRF-1 diet, Charles River Laboratories, Kanagawa, Japan) and had ad libitum access to distilled water. At nine weeks of age, rats were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 3 per group) and subjected to a single-dose oral administration. Body weight (BW) was recorded prior to dosing. The hesperidin group received a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg hesperidin dissolved in saline containing carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), The Mikan-fermented tea group received 714 mg/kg of Mikan-fermented tea extract, which contained 14 mg/g of hesperidin–equivalent to 10 mg/kg hesperidin– and was also dissolved in saline with CMC. Oral administration was performed using a gavage tube, Blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0 (pre-dose), 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post-administration. Each blood sample was collected into tubes containing EDTA, aprotinin, and chymostatin, followed by centrifugation. Plasma (100–200 µL) was separated and stored for further analysis. All animal procedures conformed to the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of the Faculty of Agriculture and the Graduate Course of Kyushu University and were approved by the university’s Animal Care and Use Committee (Permit Number: A22-104-3), in accordance with Japanese Law No. 105 (1973) and Prime Minister’s Office Notification No. 6 (1980).

2.3. Cell culture

Caco-2 cells were obtained from the RIKEN Bio-Resource Center (Tsukuba, Japan) and used between passages 50 and 60. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cultures were maintained 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% O2 air. Non-essential amino acids were purchased from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, USA). The culture medium was replaced every other day until the cells reached 80–90% confluence, typically within 5–7 days. For transport experiments, Caco-2 cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 105 cells/mL onto type I collagen-coated BD Falcon cell culture inserts (12-well plates; PET membrane, 0.9 cm2, 1.0 μm pore size; BD Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan), prepared using a collagen gel culture kit (Cell Matrix Type I-A; Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan). Each insert was placed into a 12-well plate containing 1.5 mL of culture medium on both the apical and basolateral sides. Cells were initially incubated for 48 h in seeding basal medium supplemented with MITO+™ serum extender. The medium was then changed daily for 3 days to intestinal epithelial differentiation medium to promote monolayer formation. Monolayer integrity was confirmed by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) using a multi-channel voltage/current clamp system (EVC-4000; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). Only monolayers with TEER values exceeding 400 Ω cm2 were used for subsequent transport experiments.

2.4. Transport experiments in Caco-2 cell monolayers

The transport of hesperidin across Caco-2 cell monolayers was evaluated as follows. According to our previous report (Li et. al., 2020), the culture medium on the apical side of the monolayers was removed and replaced with HBSS buffer (pH 6.0) containing either 1 μM of hesperidin or Mikan-fermented tea extract adjusted to an equivalent hesperidin concentration of 1 μM. The Mikan-fermented tea extract was prepared by dissolving in DMSO, followed by centrifugation to remove insoluble materials. The resulting supernatant was diluted with HBSS to achieve the final hesperidin concentration. The final concentration of DMSO in the transport medium was maintained at 0.05 % (v/v). TEER was measured before and after the 60-min incubation to ensure that monolayer integrity was maintained throughout the experiment (Figure S1). Only monolayers with TEER values exceeding 400 Ω cm2 were used. After a 60-min transport period, 200 μL of solution was collected from the basolateral side. To each sample, 10 μL of 5 μM taxifolin (IS) was added, and the samples were analyzed by LC-qTOF/MS to quantify transported hesperidin. To measure intracellular hesperidin accumulation, the Caco-2 cells after 60-min transport experiments were lysed with RIPA buffer and homogenized. Ethanol was added to the lysate at a 1:1 ratio, followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was filtered using an Amicon 3K filtration (14,000 g, 4 °C, 30 min), then passed through a 0.20-μm membrane filter. Fifty µL of the filtrate was mixed with 10 µL of 5 µM taxifolin and analyzed by liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-qTOF/MS).

2.5. Quantification of hesperidin and hesperetin in plasma by LC-qTOF/MS

Plasma samples (50 μL) were mixed with an equal volume of 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0). The mixture containing conjugated or non-conjugated hesperidin/hesperetin was subjected to enzymatic deconjugation to convert them to intact hesperetin form as previously described (Nectoux et al., 2019), by incubating with 25 units of sulfatase type H-1, 50 units of β-glucuronidase type H-1, and 50 units of β-glucuronidase type B-1 for 12 h at 37 °C. Prior to this treatment, 10 µL of 5.0 µM taxifolin (used as the internal standard, IS) was added to each sample. After incubation, 100 μL of ethanol was added to terminate the reaction. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 25 °C, and the resulting supernatant was collected. This supernatant was passed through an Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (molecular weight cutoff <3,000 Da; Merck Millipore Ltd., Darmstadt, Germany) by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 30 min at 25 °C. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness and reconstituted in 50 μL of 50% ethanol. The solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm Millex-LH syringe filter (Millex, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed by LC-qTOF/MS. Chromatographic separation was performed using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a Cosmosil 5C18-MS-II column (2.0 × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (solvent B), with a linear gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min, following the method described by Nectoux et al. (2019). Mass spectrometric detection was carried out using a Compact mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. The instrument settings were as follows: drying nitrogen gas flow, 8.0 L/min; drying temperature, 200 °C; nebulizer pressure, 2.0 bar; capillary voltage, 4,500 V; end plate offset, 500 V; and mass range, m/z 50–1,000. Deprotonated molecules [M-H]− of hesperidin, hesperetin, and taxifolin were detected at m/z 609.1814, 301.0707, and 303.0499, respectively, with a mass tolerance of 0.05 m/z units. Vehicle and blank controls showed no interfering peaks at the retention times of the analytes (Figure S2). Quantification was performed using calibration curves generated with the IS (1.0 nmol/mL). The calibration curve for hespedidin was y = 0.0014x + 0.0119 (R2 = 0.9993) in in vitro Caco-2 study, and for hesperetin, it was y = 0.039x + 0.3681 (R2 = 0.9973) in in vivo animal study. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Bruker Data Analysis software (version 3.2; Bruker Daltonics). Analytical validation parameters (LOD, LOQ, recovery, precision, and matrix effects) were evaluated according to the method described by Nectoux et al. (2019). We confirmed that complete hydrolysis was achieved under the present enzymatic deconjugation conditions by comparing the chromatograms of plasma samples with and without enzyme treatment (Figure S2).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three biological replicates (n = 3). Pharmacokinetic parameters, including the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to reach maximum concentration (tmax), and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0−24), were calculated based on the plasma concentration-time profiles using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, LaJolla, CA, USA). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the Student’s t-test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stat View J 5.0 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

| 3. Results | ▴Top |

3.1. Absorption of hesperidin into circulating blood after oral administration to SD rats

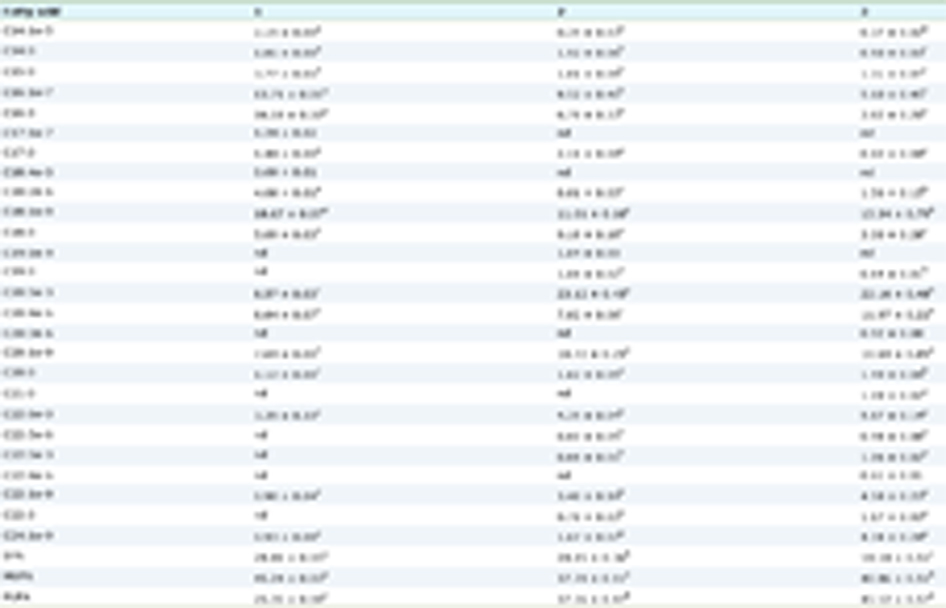

The pharmacokinetics of hesperidin (quantified as hesperetin after enzymatic deconjugation treatment) in the caudal vein following a single oral administration of either hesperidin or Mikan-fermented tea extract in SD rats. The Mikan-fermented tea group exhibited approximately a 3.7-fold higher maximum plasma concentration (Cmax, 0.84 ± 0.15 nmol/mL) compared to the hesperidin group (0.23 ± 0.11 nmol/mL). The AUC0–24 was approximately 2.4 times greater in the Mikan-fermented tea group (5.3 ± 0.02 nmol·h/mL) than in the hesperidin group (2.2 ± 0.74 nmol·h/mL) (Table 1). The tmax was reduced from 8 h in the hesperidin group to 4 h in the Mikan-fermented tea group, indicating a faster absorption rate (Figure 1). The elimination half-life (t1/2) was also shorter in the Mikan-fermented tea group (9.7 h) than in the hesperidin group (13.3 h), suggesting more rapid clearance. Collectively, these results indicate that Mikan-fermented tea enhances the oral absorption of hesperidin and facilitates its more efficient transfer into the systemic circulation.

Click to view | Table 1. Pharmacokinetic parameters of hesperidin* in the caudal vein following a single oral administration of either hesperidin or Mikan-fermented tea in Sprague-Dawley rats |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Plasma concentration-time profile of hesperidin following single oral administration of hesperidin or Mikan-fermented tea in SD rats. Plasma levels of hesperidin conjugates (measured as hesperetin after enzymatic deconjugation treatment) were determined by LC-qTOF/MS at multiple time points after administration of either 10 mg/kg hesperidin or 714 mg/kg Mikan-fermented tea (equivalent to 10 mg/kg hesperidin). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. hesperidin group. |

3.2. Effect of Mikan-fermented tea on hesperidin transport across Caco-2 cell monolayers

In the Caco-2 cell monolayer model, treatment with Mikan-fermented tea significantly enhanced the basolateral transport of hesperidin compared to treatment with hesperidin alone (p < 0.05). LC-MS analysis detected a clear hesperidin peak (m/z [M-H]- = 609.1814) in both treatment groups, confirming successful transport. However, the quantity of hesperidin transported to the basolateral side was markedly higher in the Mikan-fermented tea group (Figure 2a, p < 0.05). Moreover, intracellular accumulation of hesperidin after 60-min transport experiments was significantly lower in cells treated with Mikan-fermented tea than in those treated with hesperidin alone (p < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2b. The values were normalized to the number of viable Caco-2 cells seeded ta the start of the experiment (pmol/cell). These findings indicate that Mikan-fermented tea may reduce intracellular retention of hesperidin and promote its trans-epithelial efflux, thereby enhancing intestinal transport efficiency.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Effect of Mikan-fermented tea on hesperidin transport across Caco-2 cell monolayers. (a) Quantified basolateral transport of hesperidin after 60-min transport with either hesperidin alone or Mikan-fermented tea (each containing 1 µM hesperidin). Representative chromatograms (left) and transport data (right) are shown. The apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) were calculated to be 6.5 × 10−7 cm/s for the hesperidin group and 1.8 × 10−6 cm/s for the Mikan-fermented tea group, indicating enhanced transport efficiency. (b) Intracellular accumulation of hesperidin in Caco-2 cells after 60-min transport experiments. Representative chromatograms (left) and intracellular concentration data (pmol/cell) (right) are shown. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. hesperidin group. |

| 4. Discussion | ▴Top |

Although the beneficial effects of dietary polyphenolic compounds have been widely demonstrated in vitro, quantitative evidence supporting improved in vivo absorption remains limited (Yang et al., 2008). The present study provides the first quantitative data–using both an in vivo animal model and in vitro Caco-2 cell assay–demonstrating that consumption of Mikan-fermented tea significantly enhances the absorption of hesperidin.

A single oral administration of Mikan-fermented tea resulted in a substantial improvement in the pharmacokinetic profile of hesperidin, with approximately a 3.6-fold increase in Cmax and a 2.4-fold increase in AUC0–24 compared to hesperidin alone (Figure 1, Table 1). Notably, the elimination half-life (t1/2) was shorter in the Mikan-fermented tea group than in the hesperidin group. However, these parameters should be interpreted with caution. The apparent t1/2 calculated in this study might reflect an overlap between the absorption and distribution phases, rather than a change in systemic clearance alone. The rapid absorption observed in the tea group (tmax of 4 h) suggests that the elimination phase was more distinct. In contrast, the prolonged absorption in the hesperidin group (tmax of 8 h) may have masked the true elimination phase, resulting in an apparently longer t1/2 (flip-flop kinetics). This result is noteworthy because flavonoid bioavailability is highly influenced by co-ingested compounds, which can exert antagonistic or synergistic effects (Kamiloglu et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2008). Antagonistic interactions, such as the formation of insoluble complexes between tea catechins and milk casein, are well-documented for their inhibitory effect on bioavailability (Yildirim-Elikoglu and Erdem, 2018). Similarly, flavonoid sequestration by dietary fiber has been shown to reduce small intestinal bioaccessibility (Kamiloglu et al., 2021). Conversely, our results strongly align with literature on synergistic interactions in which the food matrix acts as an active delivery system. This matrix-based enhancement is uniquely innovative compared to existing chemical complexation strategies (e.g., cyclodextrin inclusion (Sarabia-Vallejo et al., 2023) ), as it leverages naturally occurring polyphenols to solubilize hesperidin directly within the beverage, facilitating immediate consumer application.

Such synergies often improve solubility or absorption efficiency. For example, co-ingestion of quercetin with lipids or apple pectin enhances its absorption by promoting micellarization (Lee and Mitchell, 2012). Fermentation also plays a critical role. In soy products, microbial β-glucosidase converts glycosides (e.g., daidzin) into their more bioavailable aglycones (e.g., daidzein), providing a relevant mechanistic analogy. Likewise, co-consumption of fermented milk improves carotenoid bioavailability (Morifuji et al., 2022). Therefore, the strong enhancement (2.4- to 3.6-fold) observed in our study is consistent with these known matrix-based synergistic mechanisms, indicating that Mikan-fermented tea functions as an effective natural delivery system.

Our plausible mechanism underlying the enhanced in vivo absorption is the physicochemical interaction between hesperidin and water-soluble polyphenols in the Mikan-fermented tea matrix, including catechins, theaflavins, and theasinensins. Hesperidin’s poor aqueous solubility is a major barrier to absorption, as dissolution in the gastrointestinal tract is the rate-limiting step. Passive diffusion across the intestinal epithelium depends on the concentration gradient of dissolved compounds at the epithelial surface (Lipinski et al., 2001). In this context, polyphenols in the tea matrix may act as natural solubilizers by forming no-covalent complexes with hesperidin via hydrophobic interaction and π-π stacking (Nakayama et al., 2014; Brglez Mojzer et al., 2016). This hypothesis is supported by spectroscopic and quantum mechanical analyses by Cao et al. (2015), who showed that theasinensin A in Mikan-fermented tea forms a stable 2:1 (hesperidin : theasinensin A) complex. Such complexes disrupt hesperidin self-aggregation, increasing its solubility–similar to how pharmaceutical excipients like cyclodextrins function. This enhanced solubility or stability in the aqueous phase of the small intestine likely increases the local concentration of bioavailable hesperidin, driving greater passive diffusion. This directly explains the observed improvements in pharmacokinetic parameters: a ∼3.6-fold increase in Cmax and a ∼2.4-fold increase in AUC0–24. Furthermore, the modulation of intestinal transporters by matrix polyphenols likely contributes to improved bioavailability. Hesperidin and its aglycone, hesperetin, are reported to be substrates for apical efflux transporters, including the Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) and Multidrug Resistance-associated Protein 2 (MRP2) (Brand et al., 2008). These transporters actively pump the absorbed flavonoids back into the intestinal lumen, thereby limiting their bioavailability. However, tea polyphenols present in the Mikan-fermented tea matrix, such as catechins and theasinensins (Nakayama et al., 2014), have been shown to inhibit efflux pumps (Kitagawa, 2005). Therefore, the Mikan-fermented tea matrix may exert a synergistic effect by enhancing solubility while simultaneously suppressing transporter-mediated efflux, thereby maximizing the net absorption of hesperidin. Complementary in vitro transport studies using Caco-2 cell monolayers revealed that Mikan-fermented tea significantly enhanced basolateral transport (Figure 2a) and reduced intracellular accumulation of hesperidin in 60-min transported Caco-2 cells (Figure 2b). These results further support the hypothesis that solubility enhancement reduces non-specific membrane binding and intracellular retention, facilitating more efficient trans-epithelial transport, as illustrated in Figure 3. A limitation of this study is the absence of an unfermented tea control or isolated polyphenol mixture. While our current data demonstrate the efficacy of the final Mikan-fermented tea product, future studies, including these specific controls, are warranted to strictly identify the causative components and rule out other potential matrix effects. However, the post-absorption fates of these metabolites remain unclear. As highlighted by Nectoux et al. (2019), although the blood pharmacokinetic behavior of hesperidin has been investigated, its tissue distribution and organ accumulation have not been fully elucidated. Therefore, following the confirmation of enhanced bioavailability in this study, future investigations should address the tissue distribution of hesperetin to validate its potential target organ efficacy and safety.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Proposed mechanisms of enhanced intestinal absorption of hesperidin by Mikan-fermented tea. Upper panel: In the absence of the tea matrix, hesperidin shows low water solubility and accumulates in epithelial cells, limiting its transport. Lower panel: Polyphenols in Mikan-fermented tea form non-covalent complexes with hesperidin, improving its solubility, reducing cellular retention, and enhancing trans-epithelial transport. |

| 5. Conclusions | ▴Top |

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that Mikan-fermented tea acts as a synergistic food matrix that significantly enhances the bioavailability of hesperidin. This enhancement is primarily attributed to physicochemical complexation with tea-derived polyphenols (e.g., theasinensins), which improves aqueous solubility or stability. Given that the health benefits of hesperidin are dependent on achieving sufficient plasma concentrations of absorbed hesperidin metabolites, these findings highlight the strong potential of Mikan-fermented tea as a functional food capable of delivering bioactive doses of hesperidin.

| Supplementary material | ▴Top |

Figure S1. TEER monitoring of Caco-2 cell monolayers. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values were measured before (0 min) and after (60 min) the transport experiments to assess membrane integrity. Black bars: Hesperidin alone group; White bars: Mikan-fermented tea group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). TEER values remained above the threshold (>400 Ω·cm2) at the end of the assay, confirming that monolayer integrity was maintained.

Figure S2. Specificity and efficiency of LC-qTOF/MS analysis. Representative chromatograms of hesperetin (m/z = 301.0707). Top: Plasma sample treated without β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (Non-enzyme). Only trace amounts of free hesperetin were detected. Middle: Plasma sample treated with β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (enzyme). A substantial increase in the hesperetin peak intensity confirmed the efficient hydrolysis of the conjugates. Bottom: Water blank control (Base Water). No interfering peaks were detected at the retention time of hesperetin (N.D.), confirming the specificity of this analytical method.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that no specific funding was received for this study.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

| References | ▴Top |