| Journal of Food Bioactives, ISSN 2637-8752 print, 2637-8779 online |

| Journal website www.isnff-jfb.com |

Mini Review

Volume 32, December 2025, pages 21-23

Bioactive compounds and seafood co-product valorization for sustainable lobster and snow crab bait development: a mini review

Xiaomin Zhoua, Zhen Lia, Cheng Lia, Xuezhi Shic, Zhuliang Tana, b, *

aEnterprise Research Institute of Zhejiang Industrial Group Co. LTD, Zhejiang, China

bSubait Inc, Dartmouth, NS, Canada, B2Y 4T5

cSchool of Marine Engineering Equipment, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhejiang, China

*Corresponding author: Zhuliang Tan, Subait Inc, Dartmouth, NS, Canada, B2Y 4T5 ; Enterprise Research Institute of Zhejiang Industrial Group Inc, Zhejiang, China. E-mail: ztan@subait.ca

DOI: 10.26599/JFB.2025.95032428

Received: October 8, 2025

Revised received & accepted: November 4, 2025

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The North American lobster and snow crab fishery is critical to coastal economies and for global trade. It is also heavily dependent on forage fish such as herring, mackerel, and squid as trap bait, consuming tremendous amount of them annually. This reliance exerts pressure on marine ecosystems, competes with human food markets, and raises sustainability concerns. Recent innovations have focused on developing alternative bioactive baits derived from seafood co-products, synthetic attractants and etc. This mini-review summarizes current advances in natural, artificial, and synthetic lobster baits, evaluates their efficacy, environmental and economic implications, and highlights future opportunities for developing nutritionally optimized, stable, and sustainable formulations.

Keywords: Sustainability; Co-products; Artificial; Circular Blue Economy; Bioactive Compounds

| 1. Introduction | ▴Top |

Lobster (Homarus americanus) and snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) represent two of the most economically and nutritionally valuable crustacean resources in the North Atlantic. In Canada, the value of seafood exports in 2023 reached approximately CAD $7.6 billion and the two species alone accounted for a considerable share: lobster exports were valued at about CAD $2.63 billion in 2023, and snow crab exports around CAD $1.04 billion (Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2024). These figures highlight how critical crustacean fisheries are to coastal economies and for global trade. From a nutritional standpoint, both lobster and snow crab deliver high-quality protein and important micronutrients. For example, lobster meat is rich in essential amino acids, low in saturated fat, and contains appreciable levels of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, selenium and chitin-derived bioactive compounds (Venugopal, 2021).

However, the sustainability of these two fisheries extends beyond catch quotas. Bait is also a critical input in crustacean trap fisheries, directly influencing catch efficiency and operational costs. Traditionally, forage fish such as mackerel (Scomber scombrus), herring (Clupea harengus), sardine, and squid dominate the bait market for lobster and snow crab fisheries (Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, 2024 ). For example, a recent report estimated that bait demand in Atlantic Canada in 2022 may have reached up to ∼100 000 metric tonnes for pot and trap fisheries alone. (Pisces Consulting Ltd, 2022). However, increasing demand for these species as human food and aquaculture feed has driven prices upward, creating instability in bait supply chains. Simultaneously, concerns regarding forage fish depletion due to over fishing and its ecosystem impacts have intensified (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024 ).

From a food-system and sustainability perspective, this practice represents a trophic inefficiency-using high-quality, nutrient-dense forage fish to capture crustaceans that might deliver lower caloric/biomass yield per unit of input and potentially reduce the availability of these forage fish for direct human consumption or aquaculture feed. Additionally, depletion of forage species can cascade through marine food webs, reducing prey availability for seabirds, marine mammals and larger predatory fish. Consequently, there is growing urgency to identify alternative baits that are effective, affordable, and ecologically sustainable.

Developing sustainable alternatives to traditional bait requires an interdisciplinary approach integrating food chemistry, sensory biology and fisheries management. Understanding the molecular basis of lobster and crab attraction, identifying effective bioactive compounds, engineering controlled-release systems, and scaling valorisation of seafood co-products within a circular blue economy framework are all essential. These efforts hold promise for reducing waste, lowering carbon footprint, and enhancing food system resilience-aligning the lobster and snow crab industries with global sustainability and climate goals.

| 2. Natural and synthetic bait alternatives | ▴Top |

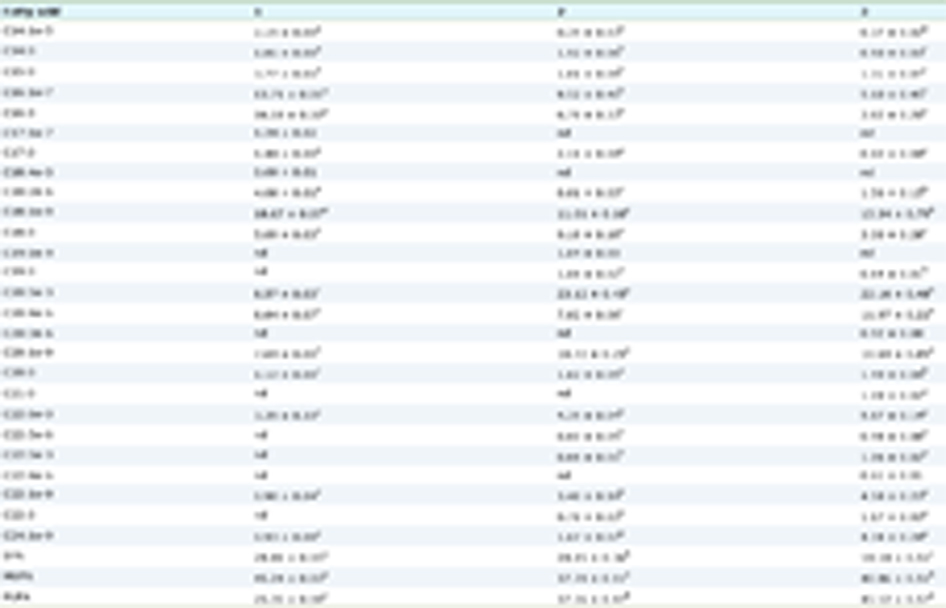

In this relation, early research explored natural alternative baits such as underutilized fishes, fish waste, poultry co-products, and agricultural residues as attractant molecules (Masilan and Neethiselvan, 2018). The Barents Sea snow crab fishery successfully tried seal fat and seal fat with skin, showing equal performance to squid bait in catch per unit efforts (Araya-Schmidt et al., 2019). In Prince Edward Island (PEI), bait substitution trials with local species (e.g., cunner, salmon waste, and green crab) demonstrated potential to alleviate reliance on traditional forage fish species like mackerel and herring. Meanwhile, synthetic approaches have attempted to mimic chemical cues naturally released from forage fish. A notable advancement was the development of a controlled-release synthetic bait matrix by Kepley Biosystems, which reliably attracted American lobster, stone crab, and blue crab in field trials (Dellinger et al., 2016). These formulations highlight the feasibility of decoupling bait supply from wild fish stocks. From a food utilization perspective, valorizing seafood processing co-products presents a blue circular economy opportunity. For instance, tuna co-products have been converted into fish silage for artificial lobster baits with promising results (Araya-Schmidt et al., 2019). SuBait Inc., for example, has pioneered the use of seafood co-products to create a proprietary “superfood for lobster.” Their formulation emphasizes effectiveness, sustainability, stability, and ease of handling, addressing year-round supply. Field validations indicate comparable or superior performance to existing products, while leveraging processing waste streams otherwise destined for landfill or compost (www.subait.ca). Studies on alternative lobster/snow crab bait materials reported in the literature are summarized in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Studies on Alternative Lobster/snow crab bait materials reported in the literature |

Acoustic lobster baits represent another innovative strategy to enhance the efficiency and sustainability of lobster fisheries by exploiting the species’ natural sensitivity to underwater sound. Unlike conventional baiting methods that rely primarily on olfactory cues from fish or shellfish, acoustic baits employ sound signals to attract lobsters toward traps, thereby reducing dependence on traditional bait sources such as herring or mackerel (Mullen, 2021). Recent studies have shown that specific frequency ranges and sound patterns associated with prey activity or natural reef environments can stimulate exploratory and foraging behavior in lobsters (Jézéquel et al., 2021). This approach not only has the potential to alleviate pressure on forage fish stocks but also contributes to the development of environmentally responsible fishing practices within the blue circular economy framework.

| 3. Ecological and biological considerations | ▴Top |

Bait availability not only affects the economy of the fishery, but it also influences lobster ecology. Studies have shown that bait-subsidized diets can alter lobster nutrition and reproductive physiology. Ovigerous lobsters fed primarily herring exhibited delayed gonad maturation and altered egg lipid profiles compared to those on more natural diets (Goldstein and Shields, 2018). Thus, alternative bait development must consider not only catch efficiency but also potential ecological side effects from bait-subsidized feeding.

| 4. Comparative effectiveness studies | ▴Top |

Field trials across regions consistently report that while many alternative baits show promise, variability in performance remains. In PEI lobster fisheries, trials comparing alternative and traditional baits found some substitutes to be less effective, though multi-species blends and processing co-products occasionally matched performance (Patanasatienkul et al., 2020). In Maine, soy-based formulations demonstrated limited success until commercial adaptation produced a product (“Clawdia’s Secret”) that extended bait longevity when combined with fresh fish. These findings underscore the need for iterative product optimization, fisher engagement and systematic study design.

| 5. Future perspectives | ▴Top |

Advancing sustainable lobster bait requires integration of food chemistry, sensory biology, and fisheries management. Key research priorities include:

- Bioactive identification: Characterizing volatile and soluble compounds responsible for lobster attraction. For example, understanding which amino acids, peptides, odorant and other molecules trigger feeding or exploratory behavior is fundamental for designing effective synthetic or co-product-based baits that mimic natural prey cues;

- Controlled-release matrices: Engineering carriers for consistent leaching under variable oceanographic conditions. Innovative gel, polymer, or biodegradable matrices can regulate diffusion rates and stability, ensuring that attractants remain active for the desired soak time even in cold, high-current waters;

- Nutritional impacts: Assessing long-term ecological effects of bait consumption on lobster health and reproduction. Evaluating whether alternative baits alter growth, energy metabolism, or reproductive outcomes helps ensure that substitutions do not compromise population fitness or product quality;

- Circular economy scaling: Expanding the valorization of underutilized seafood co-products into commercial bait production. Utilizing trimmings, viscera, and low-value species reduces waste and environmental burden while creating new revenue streams within coastal bio-economies;

- Socioeconomic adoption: Balancing cost, fisher acceptance, and regulatory frameworks to enable large-scale transition. Practical deployment depends on stakeholder trust, economic feasibility, and alignment with fishery management policies that promote sustainability without reducing profitability.

| 6. Conclusion | ▴Top |

The transition from traditional forage fish to sustainable alternative bioactive baits is both a conservation imperative and an industrial necessity. Innovations from seafood co-product valorization, synthetic attractants, and integrated formulations offer viable pathways forward. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration between food scientists, marine ecologists, fishing communities and government regulators will be essential to secure the ecological and economic sustainability of lobster fisheries in the 21st century.

| References | ▴Top |