| Journal of Food Bioactives, ISSN 2637-8752 print, 2637-8779 online |

| Journal website www.isnff-jfb.com |

Review

Volume 32, December 2025, pages 11-20

Phenolic acids: mechanisms of circadian clock-sleep regulation and metabolic modulation

Run Lia, Yue Luob, Chi-Tang Hoa, *

aDepartment of Food Science, Rutgers University, 65 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901, USA

bFood Science and Technology Programme, Department of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal-Hong Kong Baptist University, Zhuhai, Guangdong 519087, China

*Corresponding author: Chi-Tang Ho, Department of Food Science, Rutgers University, 65 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA. E-mail: ctho@sebs.rutgers.edu

DOI: 10.26599/JFB.2025.95032427

Received: October 27, 2025

Revised received & accepted: November 13, 2025

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The circadian clock and sleep are tightly linked in mammals; they regulate central and peripheral oscillators and react dynamically to sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment, affecting metabolic health. Genetic evidence highlights the impact of single-gene variants, such as Per2, Cry1, and Dec2, on a person’s sleep. On a related note, clinical studies have confirmed that chronic circadian disruption plays a role in disorders like insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and metabolic syndrome. Importantly, phenolic acids, bioactive compounds found in cereals, fruits, and coffee, are shown by growing research to influence the circadian clock and sleep. They can modulate this through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neurotransmitter-related pathways. Chlorogenic, rosmarinic, caffeic, ferulic, cichoric, salicylic, and gallic acids demonstrate differential capacities to regulate core clock gene expression, melatonin metabolism, neurotransmission, and peripheral metabolic rhythms. These interactions provide mechanistic insights into how phenolic acids may ameliorate sleep disturbances, restore circadian alignment, and improve metabolic resilience. The phenolic acids discussed in this review as promising candidates for precision strategies targeting sleep and circadian rhythm-related disorders.

Keywords: Phenolic acids; Bioactive components; Circadian clock; Sleep; Modulation mechanism

| 1. Introduction | ▴Top |

The mammalian circadian rhythm is a biological mechanism characterized by an intrinsic 24-hour cycle that enables organisms to precisely adjust to and anticipate a wide range of environmental changes (Roenneberg and Merrow, 2016). Recent research highlights the remarkable precision of the circadian clock, demonstrating its ability to adapt to external environmental cues while maintaining a stable rhythm. The clock achieves this by selectively processing signals such as changes in light timing and intensity, while filtering out insignificant noise to remain responsive to meaningful environmental alterations (Eremina et al., 2025). In advanced organisms, a circadian rhythm develops in synchrony with the surrounding environment and the day–night cycle. Sleep is regarded as a restorative process that supports immune function, energy metabolism, neurocognitive performance, hormonal regulation, and cardiovascular health. It facilitates the clearance of toxic metabolites from cells and contributes to increased life expectancy and improved quality of life. Based on behavioral and physiological criteria, sleep is divided into two states: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, which is subdivided into three stages (N1, N2, and N3), and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is characterized by rapid eye movements, muscle atonia, and a desynchronized electroencephalogram (EEG). The circadian rhythm of the sleep–wake cycle is governed by the master clock located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus. The neuroanatomical substrates of NREM sleep are located primarily in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus, whereas those of REM sleep are localized in the pons (Bon, 2020).

Phenolic acids, a secondary metabolite found in plant-based foods, are widely present in fruits, vegetables, herbs, and beverages. Daily intakes (which may exceed 100 mg) of phenolic acids are likely in the milligram range and comparable to many essential micronutrients (Eremina et al., 2025). However, these values may be underestimated because the composition databases used to calculate daily intakes often do not fully account for conjugated forms of phenolic acids. Much more focus has been placed on the potential bioactivity and nutritional importance of various phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, carotenoids, phytoestrogens, and glucosinolates. Less attention has been given to simple phenolic acids. This review explores the science behind the relationship between the circadian clock and sleep cycles, the restorative effects of phenolic acids in sleep deprivation, and the roles of phenolic acid intermediates in circadian clock genes and sleep. It also examines how phenolic acids contribute to physical healing, mental health, and the prevention of metabolic diseases. By emphasizing the critical role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the master clock that regulates this rhythm, we aim to offer insights into how phenolic acids, optimizing sleep hygiene, promoting melatonin production, and lifestyle adjustments can improve sleep quality, enhance health, and help prevent sleep-related disorders. Understanding these mechanisms highlights the profound influence of circadian rhythms on bodily restoration and potential strategies for mitigating the adverse effects of sleep disturbances.

Relevant literature was identified through a structured search of PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar and Web of Science databases, covering the period from 1990 to 2025. Search terms included combinations of “phenolic acids”, “circadian rhythm”, “clock genes”, and “sleep”. Articles were included if they addressed the molecular or physiological effects of phenolic acids on circadian regulation or sleep architecture. Reviews, clinical studies, animal models, and in vitro experiments were all considered. Studies not directly related to phenolic compounds or sleep/circadian biology were excluded.

| 2. Circadian clock and sleep | ▴Top |

The 24-hour day is a universal experience in which cognitive performance and mood fluctuate in a predictable manner. The cycles of sleep and wakefulness are closely aligned with these rhythms. The internal circadian clock functions as a biological pacemaker with a period of approximately one day (Roenneberg and Merrow, 2016).

2.1. Circadian clock in mammals-transcriptional/translational feedback loop

Almost all cells and organs exhibit circadian rhythms. In mammals, the circadian system is organized through interactions between the central clock and peripheral clocks (Lowrey and Takahashi, 2011). The central clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, serves as the primary circadian oscillator, while additional oscillators are distributed throughout other brain regions and peripheral organs such as the liver, pancreas, heart, and intestine. Peripheral clocks can function autonomously; however, their long-term coordination and synchronization depend on signals from the SCN, including light cues, hormonal secretion, body temperature, and feeding rhythms. When external rhythms are disrupted, peripheral clocks may lose synchronization, leading to oxidative stress, inflammation, and dysregulation of cellular pathways that ultimately contribute to metabolic disorders (Liu et al., 2019).

The autoregulatory transcriptional/translational feedback loop (TTFL) model is currently the most widely accepted framework for explaining the mechanisms underlying the circadian clock. In this model, transcription factors such as brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1) and CLOCK form BMAL1/CLOCK heterodimers, which activate the transcription of several negative-feedback circadian genes, including Period (Per1-3), Cryptochrome (Cry1 and Cry2), and Rev-erb (NR1D1 and NR1D2). The protein products of these genes, Per and Cry, progressively accumulate and eventually form heterodimers that inhibit the transcription of Bmal1 and Clock, thereby closing the feedback loop. The circadian clock is modulated by various internal and external cues that regulate its three principal parameters: period, phase, and amplitude. The period defines the length of the circadian cycle, the phase specifies the timing of key events within the cycle, and the amplitude reflects the strength or robustness of rhythmic oscillations (Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2019).

Genetic analyses have further elucidated the complexity of circadian traits. Shimomura et al. conducted a genome-wide interaction analysis in mice, demonstrating that multiple loci contribute to variations in circadian behavior, including phase and period (Shimomura et al., 2001). Light exposure, nonphotic stimuli, and a regulated rest–activity cycle influence both the phase and amplitude of clock gene expression, thereby shaping human circadian rhythms such as melatonin secretion, body temperature, and related physiological processes (Cajochen et al., 2003; Klerman et al., 1998). Moreover, extensive evidence indicates that the rest-activity cycle, together with the corresponding light–dark cycle, modulates the amplitude of several variables, including core body temperature, alertness, and multiple endocrine factors (Czeisler and Dijk, 2001; Dijk et al., 2012).

The phase of the circadian clock, defined as its cycle stage relative to external time, is determined by environmental cues known as zeitgebers (time-givers, external cues such as light). The clock’s response to these zeitgebers depends on both the strength of the stimulus and the circadian phase during which it is applied. As a result, zeitgebers can either advance or delay the circadian clock, thereby maintaining synchrony with the solar day (Devlin, 2002). Under normal conditions, these mechanisms confer an adaptive advantage by optimizing the timing of fundamental cellular and physiological processes and behaviors. However, inappropriate or mistimed exposure to zeitgebers, which is increasingly common in modern society, can disrupt circadian homeostasis and negatively impact human health (Roenneberg and Merrow, 2016).

2.2. Interactions between circadian clock and sleep

To further understand how these systems influence each other, the following section explores their bidirectional mechanistic interactions at the molecular and genetic levels (Figure 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. The relationship between the molecular mechanism of the human circadian clock and sleep. |

2.2.1. Mechanistic interplay between the circadian clock and sleep

The circadian clock and homeostatic sleep regulation interact to control sleep timing, architecture, and quality. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), acting as the central pacemaker, aligns the sleep-wake cycle with environmental cues, while sleep itself provides feedback on circadian gene expression. In an experiment involving male Sprague–Dawley rats subjected to 72 hours of sleep deprivation (SD), protein expression levels of BMAL1, CLOCK, and CRY1 in liver tissue were significantly downregulated, accompanied by increased oxidative stress (Li et al., 2017). A separate study in mice showed that 6-hour SD elevated PER2 expression not only in the brain but also in the liver and kidney. Notably, the SCN exhibited a limited response of PER2 to SD, whereas peripheral tissues such as the liver and kidney showed marked upregulation, suggesting that peripheral clocks are more susceptible to sleep loss than the central clock. These observations indicate that clock genes mediate the well-documented adverse effects of chronic sleep deprivation and circadian disruption on metabolic health (Curie et al., 2015). In clinical studies, depressed patients with disrupted circadian rhythms who underwent chronotherapeutic sleep deprivation therapy (SDT) demonstrated normalization of circadian-related genetic mechanisms, accompanied by improvements in sleep (Bunney and Bunney, 2013). Another human study reported that SD suppressed BMAL1 expression in young men (mean age ± SD: 23 ± 5 years), induced expression of the heat shock gene HSPA1B, and increased the amplitude of the melatonin rhythm, while the rhythms of other high-amplitude clock genes (e.g., Per1-3 and Rev-erbα) remained largely unaffected. During acute SD, the core mechanisms of peripheral oscillators were impaired, highlighting differential responses of core clock genes to sleep loss (Ackermann et al., 2013; Cedernaes et al., 2015). Overall, sleep deprivation directly regulates circadian gene expression, producing both potentially beneficial effects, such as rhythm resetting, and detrimental effects, particularly on peripheral oscillators.

2.2.2. Genetic evidence linking circadian rhythms to sleep phenotypes

Human genetic studies have convincingly demonstrated that circadian clock genes play a critical role in individual differences in sleep timing and duration. Variants of Per2 and Ck1δ are associated with Familial Advanced Sleep Phase (FASP), which is characterized by an earlier sleep-wake schedule. Conversely, mutations in the Cry1 gene delay circadian rhythms, resulting in Familial Delayed Sleep Phase (FDSP). In addition, traits such as Familial Natural Short Sleep (FNSS) are linked to mutations in Dec2 (BHLHE41) and Adrb1, enabling certain individuals to function normally with only 4–6.5 hours of sleep per night. These single-gene mutations influence both sleep timing and duration, highlighting the important role of circadian clock genes in regulating sleep behavior (Ashbrook et al., 2019).

2.2.3. Impact of circadian disruption in sleep disorders

Disruption of circadian clock-sleep alignment, whether due to acute sleep deprivation or chronic conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea (OSA), can significantly affect clock gene dynamics. Although studies specifically investigating the relationship between the circadian clock and chronotype in OSA are lacking, evidence from healthy individuals suggests a potential association. For instance, evening chronotypes exhibit higher expression levels of the Clock gene compared to morning chronotypes (Maryna et al., 2022). Moreover, differential expression of PER3, BMAL1, and CRY1 has been observed between neutral and morning chronotypes at specific time points (Faltraco et al., 2021).

Sleep deprivation decreases CLOCK and BMAL1 expression while increasing PER1, which shows positive correlations with total sleep duration and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and negative correlations with sleep latency (Sochal et al., 2024). Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the amplitude of daily oscillations in core clock genes, including Bmal1, Clock, and Cry2, is disrupted. Most circadian clock genes exhibit marked downregulation at midnight, except for Per1. Furthermore, OSA severity has been associated with genetic variants in Per3 and Cry1 (Yang et al., 2019). These findings underscore the sensitivity of circadian gene regulation to both acute and chronic sleep disturbances.

2.2.4. Circadian clock-sleep and metabolism

Both circadian misalignment and sleep disturbances are strongly associated with metabolic disorders. Translational studies have demonstrated that misalignment between internal circadian oscillators, or between internal and external rhythms, can contribute to various metabolic diseases, including diabetes and obesity (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Maury, 2019). In a study involving 60 women with normal weight, overweight, and obesity who participated in a 16-week weight loss program, DNA methylation levels at different CpG sites of the Clock, Bmal1, and Per2 genes were analyzed in white blood cells. The results indicated that methylation patterns at specific CpG sites in these three genes were significantly associated with anthropometric parameters (e.g., body mass index and degree of obesity) as well as metabolic syndrome scores (Milagro et al., 2012). The expression of metabolic genes, the activity of nuclear receptors involved in lipid and glucose metabolism, and the majority of metabolic enzymes and their transport systems are regulated by circadian rhythms. Furthermore, circadian rhythms modulate multiple metabolic processes, including glucose, cholesterol, amino acid metabolism, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, thereby maintaining energy homeostasis. Concentrations of metabolic hormones, such as insulin and leptin, also fluctuate according to circadian rhythms, underscoring that circadian genes are deeply integrated into core metabolic pathways (Huang et al., 2021). Dietary interventions, including supplementation with phenolic compounds (phenolic acids), combined with assessments of chronotype and sleep disruption patterns in personalized health plans, may help prevent and manage metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders (Avila-Román et al., 2021; Crozier et al., 2009; Rashmi and Negi, 2020).

| 3. Phenolic acids | ▴Top |

Phenolic acids are a chemically diverse group of plant-derived polyphenols and important low-molecular-weight secondary metabolites (Santos-Buelga et al., 2023). In human nutrition, cereals are a major dietary source, providing a substantial portion of antioxidant effects and contributing approximately 30% of total phenolic acids in Mediterranean diets (Laddomada et al., 2015). Phenolic acids have been shown to exert significant ameliorative effects on metabolic dysfunctions, acting as antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, antimicrobials, antidiabetics, and anticarcinogens (Kumar and Goel, 2019; Ruwizhi and Aderibigbe, 2020; Sova and Saso, 2020).

Characterized by a carboxylic acid as the primary functional group, phenolic acids are generally classified into hydroxybenzoic acids (HBAs, C6-C1), hydroxycinnamic acids (HCAs, C6-C3), and the minor class hydroxyphenylacetic acids (C6-C2) (Da Silva et al., 2025). Among these, HCAs are more widely distributed in nature than HBAs. HBAs are predominantly found in plant tissues in conjugated forms, with glucosides being the most common derivatives (Shahidi et al., 2019). Four hydroxybenzoic acids recognized as key components of lignin include p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, syringic, and protocatechuic acids, while other representative hydroxybenzoates include salicylic acid and gallic acid (Da Silva et al., 2025; Valanciene et al., 2020). In HCAs, the aromatic ring carries hydroxyl groups, whereas the side chain contains a carboxyl group (Vinholes et al., 2015). The most common HCAs are p-coumaric, caffeic, ferulic, and sinapic acids (Da Silva et al., 2025). These compounds are typically not present in free form, but occur as esters with quinic acid, tartaric acid, or various carbohydrate derivatives (El-Seedi et al., 2018; Vinholes et al., 2015) (Figure 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Chemical structures of phenolic acids discussed in this work. |

| 4. Phenolic acids modulate circadian clock genes and sleep regulation | ▴Top |

4.1. Chlorogenic acids

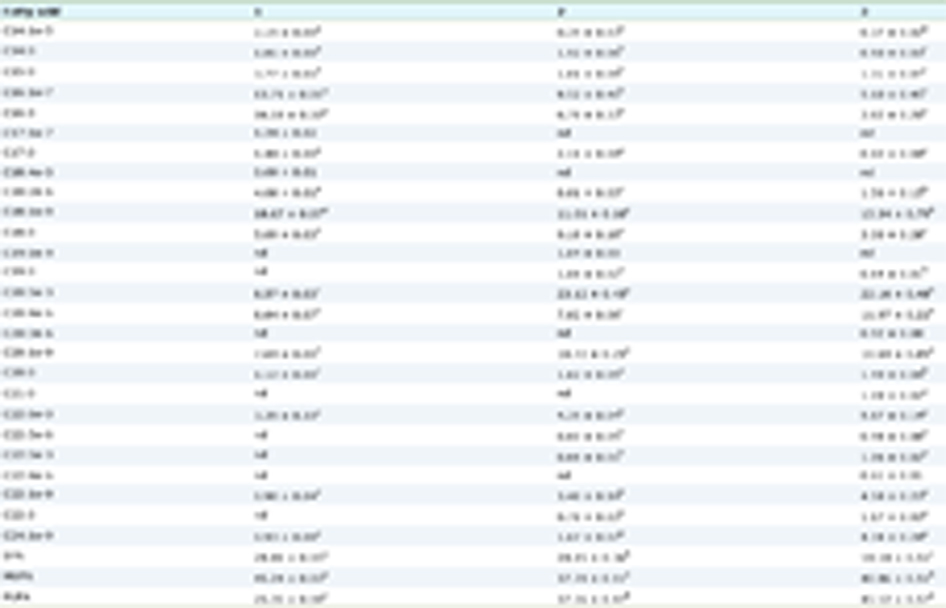

Chlorogenic acids (CGAs), also known as 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid (5-CQA), are among the most abundant hydroxycinnamic acids (HCAs) and comprise a series of compounds formed by the esterification of HCAs with 1L(-)-quinic acid. CGA is an ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid, containing two phenolic -OH groups, three aliphatic -OH groups, and one free -COOH group, which confer strong antioxidant and free radical scavenging abilities. These properties may also influence the regulation of neuroinflammation. In the digestive system, esterases hydrolyze the ester linkage, releasing caffeic acid and quinic acid, which are metabolized via distinct pathways and collectively determine the bioavailability of CGA (Botti et al., 2024; Yao et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). Caffeic acid is primarily metabolized in the liver through O-methylation and glucuronidation, similar to other phenolic acids, before excretion. It exhibits potent antioxidant activity and readily crosses the blood–brain barrier. In contrast, quinic acid mainly contributes to energy metabolism and the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids, resulting in weaker antioxidant effects and limited access to the central nervous system (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Summary of phenolic acid compounds in circadian clock-sleep regulation |

Chlorogenic acids (CGAs), abundant in coffee beans, have increasingly been recognized for their role in circadian-dependent efflux and sleep regulation. Their poor oral bioavailability influences the gut-brain axis, which follows a circadian pattern, with significantly higher absorption in the evening compared to the morning. This variation is associated with the rhythmic activity of intestinal P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux transporters, which modulate CGA bioavailability. Additionally, dopamine release can downregulate the expression and activity of these efflux transporters, thereby enhancing intestinal CGA permeation. Consequently, dopamine released from the enteric nervous system may increase the circadian dependence of CGA oral bioavailability. Furthermore, co-administration of gallic acid has been shown to reduce CGA bioavailability in both in vitro and in vivo models. In contrast, caffeic acid and ferulic acid did not affect in vitro CGA permeation, suggesting that certain dietary phenolic acids may compete with or interfere with CGA absorption (Botti et al., 2024).

Beyond absorption kinetics, human trial evidence indicates that CGAs exert multiple effects on sleep physiology. Daily intake has been associated with improved sleep outcomes, potentially through alignment with circadian rhythm regulation. In a randomized crossover trial, healthy adult males who consumed 300 mg of CGAs daily exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality and reduced morning fatigue, particularly during the later phase of the intervention. These beneficial effects were linked to enhanced sleep efficiency and decreased nighttime awakenings, suggesting a cumulative effect associated with circadian-phase-dependent sleep modulation (Ochiai et al., 2018). Mechanistically, CGAs may influence melatonin metabolism, neuroinflammatory pathways, and dopaminergic neurotransmission rhythms, all of which are closely related to circadian regulation and sleep homeostasis. In a short-term study examining 600 mg of CGA consumption in healthy adults, supplementation increased nocturnal fat oxidation without affecting overall energy expenditure. While sleep latency was reduced, CGA did not significantly alter sleep architecture, including slow-wave sleep, REM sleep, or wakefulness after sleep onset. Importantly, CGA intake enhanced parasympathetic nervous activity during the night, potentially promoting restorative sleep physiology (Park et al., 2017). Collectively, these findings support the notion that CGAs modulate the circadian clock and sleep through multifactorial mechanisms, including time-of-day-dependent absorption, regulation of neurochemical pathways, and enhancement of autonomic balance, highlighting their potential as a nutritional strategy to improve sleep quality and facilitate circadian realignment.

4.2. Rosmarinic acids

Rosmarinic acid (RA) is a phenolic acid naturally synthesized via the esterification of 3,4-dihydroxyphenyllactic acid and caffeic acid. The compound is widely distributed in many foods, particularly in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) (Petersen, 2013) and exhibits diverse biological activities, including potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, neuroprotection, and potential benefits in nervous system disorders such as epilepsy, depression, and anxiety (Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar and Hosseinzadeh, 2020; Khojasteh et al., 2020).

Evidence from preclinical and clinical studies suggests that RA can improve sleep quality and modulate circadian rhythms. In a randomized controlled trial simulating sleep deprivation (SD), a proprietary spearmint extracts high in RA (PSE, 900 mg/day for 17 days) enhanced participants’ subjective alertness, energy, and focus during 24 hours of continuous wakefulness under high cognitive demand, although objective performance outcomes were inconclusive. These findings imply that RA-rich preparations may promote cognitive resilience under conditions of circadian misalignment (Ostfeld et al., 2018).

Mechanistically, RA interacts with multiple sleep and circadian targets. In animal studies, oral RA directly binds to and activates the adenosine A1 receptor (A1R), a key target for insomnia treatment, resulting in reduced sleep fragmentation and shorter latency to NREM sleep (Kim et al., 2022). Pharmacological evidence further indicates that activation of A1R and A2AR initiates downstream signaling pathways, including Ca2+-ERK-AP-1 and CREB/CRTC1-CRE, which regulate clock genes Per1 and Per2 and modulate the circadian clock’s light response in mice (Jagannath et al., 2021; Kiesman et al., 2009; Sigworth and Rea, 2003).

RA also affects major neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory systems involved in sleep regulation, including GABA receptors, orexin receptors (OX1R), dopamine receptors, acetylcholinesterase (ACHE), melatonin MT1 receptors, and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (Zhou et al., 2024). Many of these receptors exhibit circadian oscillations, linking their activity to sleep-wake cycles. RA enhances pentobarbital-induced sleep via GABAA-ergic mechanisms: in rodents, oral doses of 0.5–2.0 mg/kg decreased locomotor activity, shortened sleep latency, and increased total sleep time, even at sub-hypnotic pentobarbital doses. EEG recordings in rats revealed that RA (2.0 mg/kg) reduced sleep–wake transitions and REM sleep, while increasing total sleep and NREM sleep (Dennis and Ronald, 2003; Kwon et al., 2016) with higher δ-wave and lower α-wave power-indicators of deeper sleep. At the cellular level, RA (0.1–10 μg/mL) increased intracellular Cl− influx in hypothalamic neurons, upregulated glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) expression, and elevated most GABAA receptor modulation, except β1 (Kwon et al., 2016).

RA’s interaction with MT1 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and thalamus suggests a role in regulating sleep initiation and circadian phase timing (Gobbi and Comai, 2019; Zhou et al., 2024). Its effects on OX1R, a wake-promoting receptor rhythmically regulated by the SCN, further indicate potential for restoring arousal–sleep balance (Sakurai, 2007). Collectively, these findings emphasize RA’s dual role in improving sleep architecture and modulating circadian output pathways, highlighting its potential in treating sleep disturbances associated with circadian dysregulation.

4.3. Caffeic acid

Recent research on circadian clock genes and aging-related pathways highlights the significant influence of caffeic acid (CA) on cellular aging processes and circadian rhythm regulation (Okada and Okada, 2020). CA has been shown to modulate clock gene expression in both young and aged fibroblasts. In young fibroblasts, treatment with 2.5 μM CA significantly increased mRNA levels of Per1 (1.3-fold), Sirt6 (1.6-fold), and NR1D1 (5.4-fold), whereas a higher concentration (25 μM) further elevated Sirt6 expression (2.5-fold). In aged fibroblasts, CA induced a dose-dependent increase in Bmal1 and NRF2 mRNA expression (p < 0.01), with Per1 and Sirt6 showing upward trends. Notably, both young and aged cells exhibited significant reductions in Sirt1 and GDF11 mRNA expression following CA treatment. At the protein level, CA, along with quercetin, markedly increased BMAL1 expression in aged fibroblasts. This observation is particularly relevant, as the main circadian transcriptional activators, CLOCK and BMAL1, directly bind to the SIRT1 promoter to enhance transcription (Zhou et al., 2014), and SIRT1, especially in the brain, regulates central circadian rhythms via activation of CLOCK/BMAL1-driven transcription (Chang and Guarente, 2013).

Additional evidence from in vivo studies in Drosophila demonstrates that chronic sleep deprivation (CSD) disrupts intestinal homeostasis and immune function through the IMD signaling pathway. CA supplementation mitigated CSD-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction, restored acid-base balance, and downregulated pro-inflammatory gene expression (e.g., Dpt, AttA, Mtk), suggesting that CA may reduce peripheral inflammation and support circadian stability during sleep deprivation (Yang et al., 2025).

Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that CA enhances melatonin bioavailability, a major circadian hormone regulating the sleep-wake cycle, by inhibiting its hepatic metabolism mediated by the CYP1A enzyme family. In rat liver microsome assays and oral administration experiments, CA increased systemic melatonin levels by up to 114% while reducing apparent clearance. Caco-2 monolayer assays confirmed that CA does not interfere with intestinal melatonin absorption, suggesting its action is mediated primarily via metabolic inhibition. This prolonged activation of melatonin receptors (MT1/MT2) may enhance melatonin’s circadian and sleep-promoting effects (Jana and Rastogi, 2017). Collectively, these findings reveal multiple mechanisms by which CA may regulate circadian rhythms and improve sleep quality.

4.4. Ferulic acid

Ferulic acid (FA; 4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid) is a widely distributed plant-derived phenolic acid, found particularly in cereals, grains, and the roots of fruits and vegetables (Pyrzynska, 2024). FA has demonstrated sedative and hypnotic effects in animal models, primarily mediated through serotonergic mechanisms, as suggested by its interaction with 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and the abolishment of its effects following pretreatment with para-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) (Tu et al., 2012). Given serotonin’s pivotal role in circadian regulation—especially within the SCN-pineal-melatonin axis (Hibi, 2023), these findings indicate that FA may modulate circadian outputs, including sleep duration and onset. Although FA exhibits limited penetration across the blood-brain barrier, its efficient absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and peripheral bioactivity provide a potential platform for influencing circadian-related sleep phenotypes via peripheral-to-central signaling mechanisms.

4.5. Cichoric acid

Recent studies indicate that cichoric acid (CA) attenuates hepatic lipid accumulation and modulates the circadian expression of core clock genes, notably Bmal1. The critical role of Bmal1 in mediating the metabolic benefits of CA is highlighted by findings that Bmal1 silencing abolishes these protective effects, suggesting a circadian clock-dependent mechanism. Mechanistically, CA activates the Akt/GSK3β signaling pathway, suppresses the expression of key lipogenic genes such as fatty acid synthase (FAS) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and restores circadian rhythmicity under lipid-induced metabolic stress. Collectively, these findings reveal a functional clock–metabolism regulatory axis through which CA may enhance metabolic homeostasis (Guo et al., 2018).

4.6. Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid (SA) exhibits notable sleep-promoting effects in preclinical models. In ketamine-induced sleep tests, SA administered at 30 and 300 mg/kg significantly prolonged sleep duration (p < 0.05), indicating a direct hypnotic action. This effect may be mediated, at least in part, by enhancement of GABA-ergic neurotransmission. Specifically, the 30 mg/kg dose of SA upregulated glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) expression in the ventral subiculum of the hippocampus, a brain region implicated in anxiety regulation. Since GAD1 encodes glutamate decarboxylase 67 (GAD67), the key enzyme for GABA synthesis, these results suggest that SA enhances inhibitory tone via increased GABA production, a mechanism shared with classical sedative-hypnotics. Additionally, the same dose demonstrated anxiolytic effects, which may further facilitate sleep by alleviating anxiety-related disturbances. Collectively, these findings support a dual mechanism for SA in sleep improvement, involving both direct GABA-ergic modulation and anxiolysis (Motaghi et al., 2021).

4.7. Gallic acid

Gallic acid (GA; 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) is a naturally occurring trihydroxybenzoic acid abundant in various dietary sources, including berries, grape seed, green tea, and wine. In grape seed proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE; 17.7 ± 2.0 mg GA/g extract), GA contributes to the regulation of liver lipid metabolism through microRNA modulation. In Wistar rats, GSPE suppressed the expression of hepatic miR-33a and miR-122 in a dose-dependent manner, which also reduced postprandial lipemia. Since miR-33 and miR-122 are key regulators of liver lipid homeostasis (Baselga-Escudero et al., 2014a), these findings support a role for GA-containing GSPE in modulating liver lipid metabolism.

MicroRNAs are responsive to photic cues, and specific miRNAs (Cheng et al., 2007), such as miR-27b-3p, have been shown to regulate the rhythmic expression of Bmal1 in mouse liver, thereby influencing the circadian clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (Zhang et al., 2016). In vitro studies further demonstrate that GA and the procyanidin dimer B2 downregulate miR-122 expression in HepG2 cells at 50 µM and modulate miR-33a in FAO cells (Baselga-Escudero et al., 2014b; Manocchio et al., 2022). However, direct evidence that GA alone regulates circadian genes remains limited.

Dietary polyphenols, including phenolic acids in GSPE, also modulate circadian rhythms in peripheral metabolic tissues. In a rat study, GSPE corrected liver circadian rhythm disruptions induced by a cafeteria diet (CAF). The extract restored the rhythm of core liver clock genes (Bmal1, Per2, Cry1, Rorα), with the most pronounced effects observed for rhythms controlling ROS production and antioxidant gene expression. Notably, the timing of administration influenced outcomes: GSPE had different effects when given at ZT0 (day) versus ZT12 (night) (Rodríguez et al., 2022).

Tea polyphenols (TP), containing high levels of GA (67.0 ± 2.2 mg/g), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and epicatechin gallate (ECG), have been shown to reduce oxidative stress via circadian clock-dependent mechanisms. In models of H2O2-induced oxidative stress, TP restored the amplitude and phase of core clock genes, reversed mitochondrial dysfunction, and activated the Nrf2/ARE/HO-1 antioxidant pathway by enhancing Nrf2 nuclear translocation. Importantly, silencing Bmal1 abolished all these effects, highlighting TP-and particularly its phenolic acid components-as bioactive nutrients linking circadian regulation to cellular redox homeostasis (Qi et al., 2018).

| 5. Conclusion | ▴Top |

Phenolic acids play crucial roles in human metabolic health by contributing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, and anticancer effects. Beyond their metabolic benefits, accumulating evidence highlights their involvement in the regulation of circadian clock genes and sleep physiology. Specifically, phenolic acids-particularly chlorogenic, rosmarinic, caffeic, ferulic, cichoric, salicylic, and gallic acids-modulate circadian gene expression, sleep architecture, and metabolic outcomes via multiple pathways. These compounds interact with neurotransmitter systems (e.g., GABA-ergic, adenosinergic, serotonergic), melatonin metabolism, and redox-sensitive signaling, while also influencing epigenetic modifications and microRNA-mediated regulation of circadian oscillators.

It is important to note that this review has certain limitations. For some phenolic acids, direct evidence demonstrating their influence on the circadian clock or sleep remains limited. Reported effects are primarily derived from studies on extracts in mixed forms or from correlations inferred from existing literature, as exemplified by gallic acid. Despite these limitations, phenolic acids may function as chrono-nutritional modulators, offering dietary strategies to improve sleep quality, restore circadian alignment, and mitigate metabolic dysfunctions associated with circadian misalignment.

Future research should focus on chronopharmacological studies to identify the best timing for phenolic acid intake and to examine its interactions with established sleep medications. Including multi-omics approaches may help uncover molecular pathways involved in circadian regulation. Personalized interventions based on chronotype and genetic differences should also be explored to improve effectiveness.

Using phenolic acids as a dietary approach to modulate circadian rhythms and sleep may confer significant physiological benefits, including enhanced sleep quality, improved metabolic health, and neuroprotection, all with a relatively low risk of adverse effects. Given the increasing global prevalence of metabolic and sleep disorders, understanding the role of phenolic acids in circadian biology is critical for developing effective nutritional and therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

This is supported by NJAES Project # NJ10125, supported by the USDA-National Institute for Food & Agriculture. Run Li acknowledges support from China Scholarship Council.

| References | ▴Top |