| Journal of Food Bioactives, ISSN 2637-8752 print, 2637-8779 online |

| Journal website www.isnff-jfb.com |

Review

Volume 32, December 2025, pages 1-10

Olive oil by-products as sustainable sources of bioactive polyphenols and peptides: from molecular mechanisms to nutraceutical applications for cardiovascular disease prevention

Carmen Lammi*, Carlotta Bollati, Melissa Fanzaga, Maria Silvia Musco, Lorenza d’Adduzio

Department of Pharmaceutical Science – Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Mangiagalli, 25 20133 Milano, Italy

*Corresponding author: Carmen Lammi, Department of Pharmaceutical Science – Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Mangiagalli, 25 20133 Milano, Italy. E-mail: carmen.lammi@unimi.it

DOI: 10.26599/JFB.2025.95032426

Received: September 30, 2025

Revised received & accepted: October 23, 2025

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) is worldwide recognized as intrinsically functional food. Its health-promoting activity, mainly in the cardiovascular prevention, is certainly associated to its composition (oleic acid and secondary metabolites, like phenolic compounds). Recently, olive oil production by- and co-products, such as olive mill wastewater, pomace, leaves, and seeds, are emerging as promising sources of food bio-actives. Indeed, these raw materials offer new opportunities for the nutraceutical and the functional food sectors. In this context, this review provides a preliminary overview of the phytochemistry, biological properties, and mechanisms of action of phenolic compounds and peptides derived from olive oil by-products. We also underline the role of their intestinal bioavailability, discuss their applications and future perspectives on how these bioactives can promote innovation in nutraceutical sector.

Keywords: Bioactive peptides; Olive seed; Food by-products; Olive oil polyphenols

| 1. Introduction | ▴Top |

Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, obesity and hypertension are among the main risk factors correlated to metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Balakumar et al., 2016). Nowadays there is a growing interest in dietary patterns and nutraceuticals/functional foods rich in bioactive compounds as strategy to provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition, able to counteract the development of metabolic diseases (Cena and Calder, 2020). The Mediterranean diet is characterized by the daily intake of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO), which is a well known functional food, thanks to its lipid composition and phenolic fraction, exert health promoting effect (Aparicio-Soto et al., 2016; Lammi et al., 2020; Tsimihodimos and Psoma, 2024). In the 2011, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) released a health claim related to the protection of blood lipids from oxidative stress, recognizing the health benefits of olive oil polyphenols, (EFSA, 2011). Olive oil production chain produces large quantities of by-products, such as wastewater (OMW), olive seeds, pomace, and pruning residues. These by- and/or co-products have an environmental impact especially in the mediterranean countries. It is interesting to consider that, nearly 98% of the phenolic compounds of the olive fruit remain in the OMW rather than in the final oil (Enaime et al., 2024; Hassen et al., 2023). Hence, it is evident that these by-products are a valuable source of bioactive molecules, which can be recovered and valorized to obtain ingredients with high added value to apply in the pharmaceutical, nutraceutical and cosmetic fields (Selim et al., 2022). Indeed, the olive oil by-products valorization is perfectly in line with the circular economy principles and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of Agenda 2030, particularly those related to responsible production and consumption, climate action and good health. In light with this consideration, this review aims to provide an overview of the bioactive potential of olive oil polyphenols and seed-derived peptides, highlighting their mechanisms of action, bioavailability and translational applications. The integration of advanced technologies such as peptidomics, metabolomics and artificial intelligence-based bioactivity prediction could accelerate the discovery and development of this research field. Peptidomics allow the systematic identification and characterization of peptides, while metabolomics provide a comprehensive understanding of the metabolic changes and physiological effects they induce. Together, these approaches optimize the transition from bioactives obtaining and characterization to functional validation, ultimately supporting the development of market-ready nutraceutical and functional foods.

In this review, a literature search was conducted between June and September 2025 using PubMed and Google Scholar, focusing on extra virgin olive oil, olive by-products, and their bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols and peptides with reported antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic effects. Keywords included: “olive oil polyphenols”, “oleuropein”, “hydroxytyrosol”, “olive seed peptides”, “bioactive peptides”, “soybean peptides, “lupin peptides”, “DPP-IV inhibition”, “cholesterol metabolism”, “gut microbiota”, and “metabolic effects”. Publications from 2004 to 2025 were considered. After duplicate removal and screening for relevance, 81 peer-reviewed articles in English reporting in vitro, in vivo, clinical, or review evidence on the biological activities and health-promoting potential of olive-derived bioactives were retained for detailed evaluation.

| 2. Polyphenols from extra virgin olive oil and by-products | ▴Top |

Olive oil polyphenols encompass a structurally diverse family of secondary metabolites, including secoiridoids, phenolic alcohols, flavonoids, lignans and phenolic acids (Rodríguez-López et al., 2020). Secoiridoids such as oleuropein, oleocanthal, and oleacein are unique to the Oleaceae family and are particularly abundant in EVOO (Lozano-Castellón et al., 2020). Hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol, derived from the hydrolysis of oleuropein and ligstroside, are among the best-studied phenolic alcohols, known for their high bioavailability. Flavonoids such as apigenin and luteolin, though less abundant, contribute additional antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. For polyphenols in olive oil to exert their biological functions, they must reach their sites of action and interact with specific molecular targets. In humans, their absorption has been evaluated indirectly through the measurement of increased plasma antioxidant capacity (Pérez-Jiménez et al., 2009). Nevertheless, their bioactivity depends on both absorption and metabolism-complex processes that remain only partially understood. These steps are influenced by several factors, including physicochemical properties, structural features, polarity, degree of polymerization or glycosylation, and solubility. In particular, the molecular structure of polyphenols plays a decisive role in intestinal absorption. Among the structural parameters most frequently highlighted are esterification, glycosylation, and molecular weight. The health benefits of olive polyphenols are supported by a robust body of in vitro, in vivo and clinical evidence (Liva et al., 2025; Martín-Peláez et al., 2013; Serreli et al., 2024). Antioxidant activity is among the most widely documented, with hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein shown to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses and reduce lipid peroxidation (Bartolomei et al., 2022; Tamburini et al., 2025). Anti-inflammatory properties are mediated through the suppression of NF-κB signaling, inhibition of COX-2, and modulation of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (Pojero et al., 2022; Santangelo et al., 2017). Cardiovascular protection is evident through multiple mechanisms: reduced (Low-Density Lipoprotein) LDL oxidation, improved HDL function, reduced triglycerides and enhanced endothelial function (Lüscher et al., 2014). Furthermore, antidiabetic effects include the inhibition of Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), improved secretion of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1), and enhanced insulin sensitivity via AMPK activation (Bartolomei et al., 2022). Neuroprotective and anticancer effects, though still under investigation, further underscore the multifunctionality of these compounds. Bioavailability is a key determinant of the biological activity of olive polyphenols. Hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol are efficiently absorbed in the small intestine, reaching plasma concentrations within one-hour post-ingestion (Ciupei et al., 2024). They undergo phase II metabolism to glucuronides and sulfates, which retain significant bioactivity (Ciupei et al., 2024). Secoiridoids, on the other hand, are less efficiently absorbed due to their larger molecular weight and hydrophobicity but are hydrolyzed into smaller, more bioavailable derivatives (López de las Hazas et al., 2016; Pinto et al., 2011). The interplay between polyphenol metabolism, gut microbiota and systemic bioactivity remains an active area of research, highlighting the complexity of assessing nutraceutical efficacy (Mahdi et al., 2025; Singh et al., 2019). Olive oil by-products such as OMW, pomace, and leaves are rich in polyphenols, often at concentrations higher than in EVOO itself (Paulo and Santos, 2021). Recovery strategies include solvent extraction, membrane filtration, supercritical CO2, ultrasound-assisted extraction, and enzyme-assisted methods. Purified extracts have shown potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hypocholesterolemic activities (Dauber et al., 2023). For instance, phytocomplex obtained from OMW, has demonstrated the ability to inhibit 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase), upregulate Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR), and downregulate Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) in HepG2 cells, as well as improve lipid profiles in hypercholesterolemic mice (Bartolomei et al., 2021; Lammi et al., 2020). These findings emphasize the translational potential of olive by-product polyphenols as sustainable nutraceutical ingredients. Table 1 summarizes the key phenolic compounds found in EVOO and its by-products, their principal biological effects, and the type of evidence supporting their activities. Hydroxytyrosol stands out with EFSA-approved claims for protection of LDL from oxidative stress.

Click to view | Table 1. Major phenolic compounds in EVOO and their biological activities |

| 3. Bioactive peptides from olive seed proteins | ▴Top |

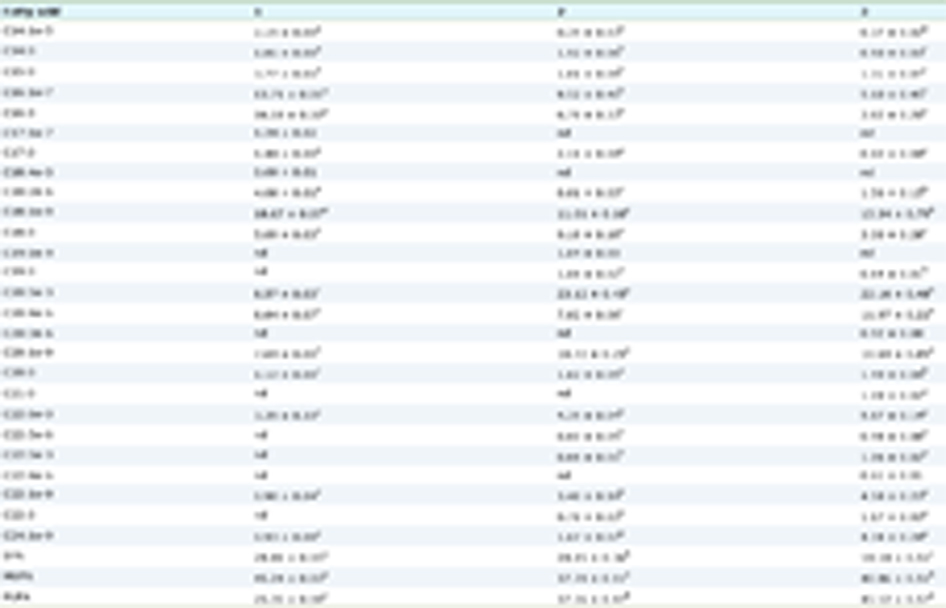

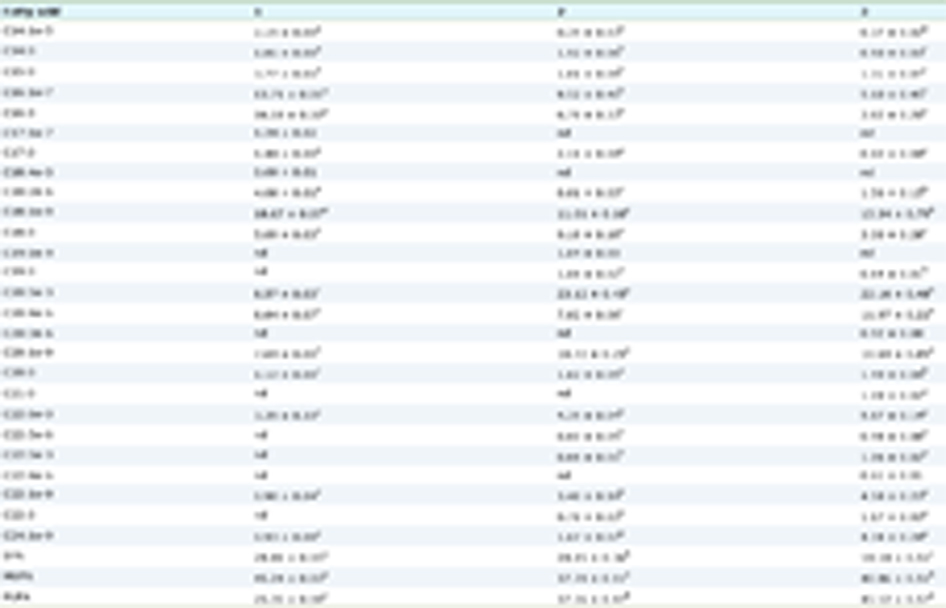

The use of food-derived bioactive peptides for the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals it is becoming an attractive practice, and currently, products containing peptides with health-promoting effects are accessible on the market (Fan et al., 2022). Over the last ten years, a considerable number of scientific investigations have highlighted the beneficial effects of protein hydrolysates and peptides recovered from a wide range of food by-products, including antimicrobic, antihypertensive and especially antioxidant and antidiabetic. Among plant-based sources, the most relevant for bioactive peptides production are cereals, legumes and seeds. Soybean meal, produced in vast quantities, contains significant protein levels and is the most widely used vegetable protein source. Cereal by-products, such as those from wheat, oats, and rice, also contribute considerable amounts of protein. Additionally, pomace and stones derived from fruit and vegetable processing can contain notable protein fractions, making them another potential resource for bioactive peptides production. During oil production, olive seeds are often discarded, even though they represent a valuable source of proteins, accounting for approximately 17% of dry weight. The predominant protein fraction belongs to the 11S storage globulin family, rich in essential amino acids such as arginine and valine (De Dios Alché et al., 2006). This amino acid profile supports the release of bioactive peptides upon enzymatic hydrolysis, making olive seeds a promising resource for sustainable nutraceutical development. The most applied approach for generating bioactive peptides from olive seed proteins is enzymatic hydrolysis (Esteve et al., 2015; Mora and Toldrá, 2023). Alcalase is a serine endopeptidase, while papain is cysteine protease derived from the papaya fruit. Both are largely employed for bioactive peptides production from animal and plant sources. Starting from olive seed, the enzymes have been shown to produce distinct peptide profiles, and consequently, different biological activities. Peptidomic analysis using high-resolution mass spectrometry has identified medium- and short-sized peptides with predicted antioxidant, antidiabetic and hypocholesterolemic properties. Bioinformatics tools facilitate ranking of peptide sequences based on in silico activity prediction, guiding the selection of candidates for further validation (Bartolomei et al., 2022, 2024). Table 2 shows the enzymatic hydrolysates of olive seed proteins, obtained by hydrolyzing them by using Alcalase (0.15 UA/g, pH 8.5, 50 °C, 4 h) and Papain (100 UA/g, pH 7.0, 65 °C, 8 h) food-grade enzymes in optimized conditions for producing Alcalase hydrolysate (AH) and Papain hydrolysate (PH), respectively, thus highlighting their hypocholesterolemic, antidiabetic, and antioxidant effects in cellular models such as HepG2 and Caco-2. Both AH and PH demonstrate capacity for transepithelial transport, supporting their bioavailability. Interestingly, PH peptides were found to be more abundant in the BL chamber compared with AH peptides, suggesting that different enzymatic processes can have an impact on both final peptidomic profile of the food protein hydrolysates and on their bioavailable fraction.

Click to view | Table 2. Bioactive properties of olive seed protein hydrolysates |

3.1. Biological activities of olive seed peptides

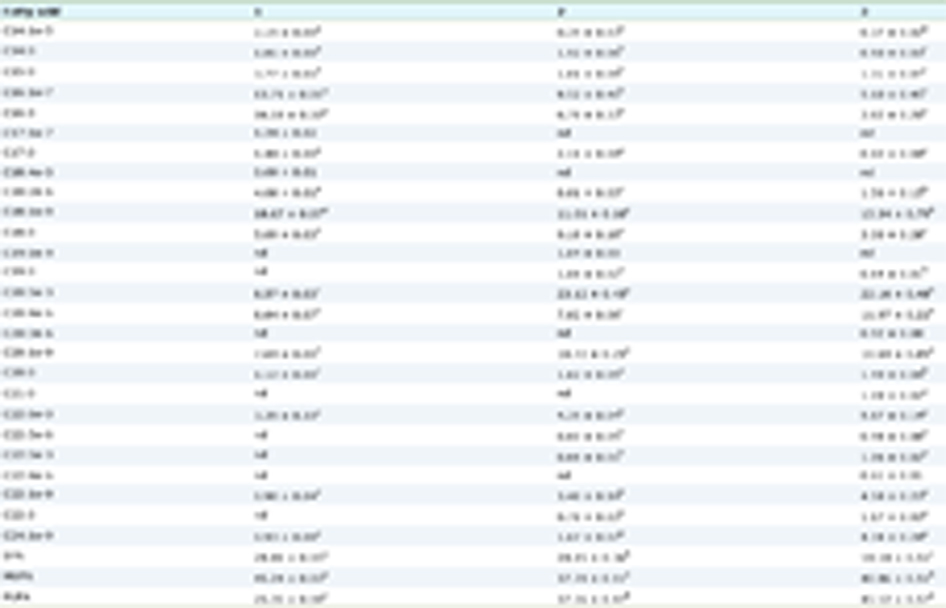

The bioavailability of bioactive peptides is crucial to their biological functionality, but often limited by low stability, short half-life, and poor ability to cross physiological barriers. Once ingested, peptides may interact with the food matrix, undergo hydrolysis in the stomach, and be further degraded by pancreatic enzymes, microbiota, and pH changes. Resistant peptides can reach the intestine, where they are absorbed through different pathways, including PepT1-mediated transport, paracellular transport, transcytosis, and passive diffusion. Each pathway favors specific peptide properties, and uptake can vary depending on peptide concentration. Animal models, especially rats, are commonly used to study peptide absorption, but they involve invasive and ethically problematic methods. To overcome these limitations, in vitro models can be employed, such as simulated digestion systems and cell monolayers for peptides bioaccessibility and bioavailability evaluation. Among these, Caco-2 cells are the most widely used, as they differentiate into enterocyte-like cells with brush border, tight junctions, and active transporters (Lea, 2015). Despite their limitations, they effectively mimic intestinal epithelium and allow measurement of peptide transport between apical and basolateral compartments. Studies using Caco-2 cells have confirmed absorption of peptides derived from fish, meat, cereals, and plant by-products, supporting their potential as functional ingredients. Olive seed protein hydrolysates exert multifunctional biological effects. Antioxidant activity includes direct radical scavenging as well as cellular protection against H2O2-induced ROS and lipid peroxidation in Caco-2 and HepG2 cells. Antidiabetic activity potential arises from the ability of olive seed peptides to reduce the DPP-IV activity and to stabilize GLP-1, thereby enhancing insulin secretion and glycemic control. The cholesterol-lowering activity is exerted by dual inhibition of HMG-CoAR and the impairment of PCSK9/LDLR interaction, resulting in increased LDL uptake by human HepG2 cells. Bioavailability studies using Caco-2 monolayers have demonstrated the ability of olive seed peptides to cross the intestinal barrier. The detection of peptides in the basolateral compartment confirms their potential systemic bioactivity. In silico toxicity assessments have further confirmed the safety of these peptides, supporting their potential regulatory acceptance as novel food ingredients (Bartolomei et al., 2022, 2024). The cholesterol-lowering properties of olive seed peptides show similar mechanism of action of other well-studied plant protein hydrolysates, in this context, both lupin and soybean protein hydrolysates stand out. Lupin α-conglutin derived peptides demonstrated to modulate cholesterol metabolism by competitively inhibiting HMG-CoAR activity and improving the LDLR protein levels in human hepatic HepG2 cells (Lammi et al., 2014; Lammi et al., 2016a). Interestingly, in vivo preclinical studies on animal models confirmed their hypocholesterolemic effects, and clinical trials performed on healthy volunteers, highlighted significant reductions in total and LDL cholesterol, alongside improvements in glycemic control, suggesting a dual role in cardiovascular and metabolic disease prevention (Cruz-Chamorro et al., 2023; Santos-Sánchez et al., 2022). Peptides derived from soybean β-conglycinin and lunasin have demonstrated the ability to reduce plasma cholesterol levels through multifunctional mechanisms, i.e. intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibition, hepatic cholesterol synthesis reduction, and mature LDLR protein level improvement on the surface of human hepatocytes (Kim et al., 2021). In addition, soybean peptides exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, further contributing to cardiovascular protection (Chatterjee et al., 2018). Indeed, the cholesterol-lowering properties of soybean derived peptides is clinically supported, leading to regulatory health claims in several regions (Blanco Mejia et al., 2019). Compared with lupin and soybean, olive seed peptides represent a novel and less-explored source. Current evidence from in vitro studies indicates that olive peptides share common mechanisms such as HMG-CoA reductase inhibition and PCSK9/LDLR modulation but also display additional features such as GLP-1 stabilization and antioxidant capacity (Table 3). While lupin and soybean have been validated as sources of multifunctional peptides in both animal models and human clinical trials, olive-derived peptides remain at the preclinical stage and, for this reason, future in vivo and human studies are required for obtaining the proof of concept regarding their potential health promoting effects.

Click to view | Table 3. Comparative overview of hypocholesterolemic peptides from olive, lupin, and soy |

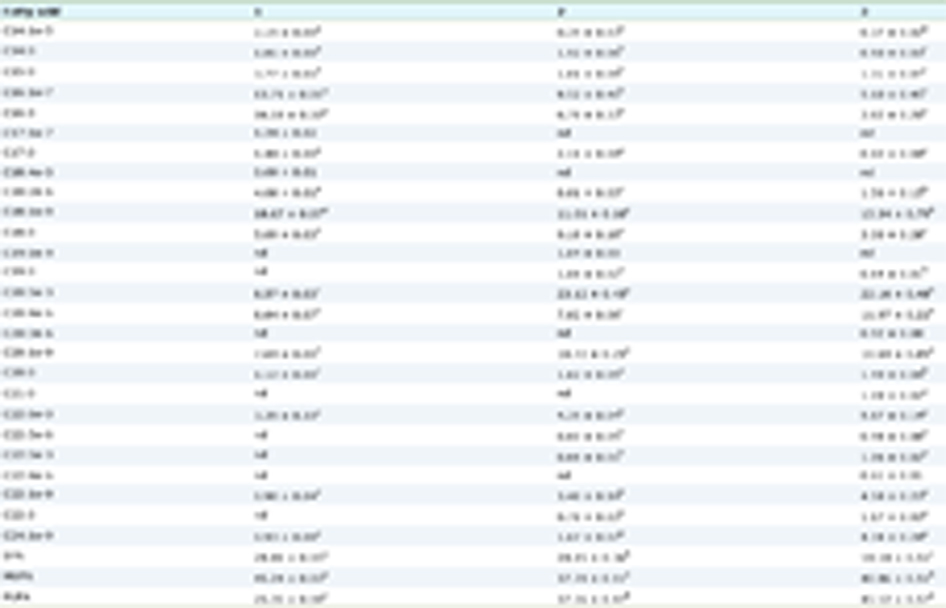

Table 4 presents a comparative overview of hypocholesterolemic effects across olive, lupin, and soy protein hydrolysates. Interestingly, comparing the different food matrices, it appears clear that olive peptides, which are currently validated at preclinical level, display a broad spectrum of actions that combine lipid-lowering, antioxidant, and incretin-modulating effects. Peptide extracts from olive seed (Olea europaea L.) are considered novel foods in the European Union, as they have no documented history of human consumption prior to 15 May 1997 (AESAN, under EU Regulation 2015/2283). This highlights their potential as a novel bioactive ingredient with unique nutritional and functional properties worthy of further investigation (https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/novel-food/consultation-process-novel-food-status_en#P). In this context, Prados and colleagues reported that the olive genotype can significantly affect the hypolipidemic features of the final olive seed hydrolysate. Remarkably, by analyzing raw olives belonging to 20 different varieties they observed significant differences in lipid-lowering properties, including the inhibition of HMG-CoAR and cholesterol esterase enzymes, and variations in micellar cholesterol solubility reduction (Prados et al., 2020). Differently, Bartolomei and colleagues (2024) demonstrated that using three different Italian olive cultivars (Frantoio, Leccino, and Moraiolo) as sources of seeds and producing two distinct hydrolysates from the same pooled cultivars using either the enzyme Alcalase or Papain, resulted in peptide mixtures with comparable bioactivity, AH and PH respectively, indicating that the observed bioactivity is not cultivar-dependent. However, differences in bioactivity emerged between hydrolysates produced with the two enzymes, particularly PH exhibits a notably higher hypoglycemic activity compared to the AH. These aspects highlight the relevance of selecting optimized conditions by both choosing the best cultivar and enzyme process for obtaining bioactive hydrolysates starting from olive seed raw material.

Click to view | Table 4. Comparative hypocholesterolemic effects of olive, lupin and soy protein hydrolysates |

3.2. Peptidomic profile and bioactivity of olive seed hydrolysates

An advanced peptidomic analysis of olive seed protein hydrolysates obtained using alcalase and papain and subjected to ultrafiltration with < 3KDa cut-off, indicated the enrichment of both medium- and short-sized peptides derived from 11S globulins. The qualitative peptidomic profiling obtained using UHPLC-HRMS, demonstrated enzyme-specific peptide fingerprints, indicating distinct peptide distributions in AH and PH. In addition, both hydrolysates exhibited intestinal transepithelial transport, since olive seed peptides were detected in the basolateral compartment of a Transwell system where human Caco-2 cells have been differentiated. The peptidomic fingerprint indicated the presence of multiple short peptides, mainly di- and tripeptides, along with several medium-sized sequences, metabolically stable once in contact with peptidases expressed by in vitro brush border, and able to be transported by intestinal cells (Bartolomei et al., 2022). Notably, as reported in Figure 1, for AH 360 peptides were detected on the apical side (AP) and 199 on the basolateral side (BL), while PH showed 358 and 252 peptides, respectively. When compared with the original mixtures, 134 peptides were found to be stable and present in BL compartment for AH, whereas 218 peptides were identified in BL for PH, indicating a higher stability and potential for absorption in the papain hydrolysate (Bartolomei et al., 2024). The most abundant detected peptides contain hydrophobic residues such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine, which can be correlated with cholesterol-lowering and antioxidant activities, respectively (Boachie et al., 2018; Ifrim et al., 2018). Other peptides provide in their sequence the amino acids proline, which confer conformational rigidity and resistance to enzymatic degradation, supporting their intestinal stability and increased biovailability (Shevchenko et al., 2019). The presence of aromatic residues (tyrosine and phenylalanine) was positively linked with radical scavenging ability, reinforcing the antioxidant potential of these hydrolysates (Aluko, 2012) Both AH and PH increased total LDLR protein levels through activation of the transcription factor SREBP-2 in hepatocytes. This molecular effect is translated from a functional point of view in an improved ability of hepatic cells to uptake extracellular LDL. Importantly, neither hydrolysate modulated HNF1-α, meaning they did not directly suppress PCSK9 expression. This mechanism distinguishes olive seed peptides from lupin-derived peptides, which can also act via HNF1-α to reduce PCSK9. The multifunctional nature of olive peptides, however, includes not only LDLR regulation but also antioxidant and GLP-1 stabilizing activities, expanding their potential health benefits. Correlation analyses between the peptidomic profile and bioactivities revealed that fractions enriched in low-molecular-weight peptides (<1 kDa) had the strongest effects on LDLR augmentation and oxidative stress reduction. Fractions enriched in peptides containing arginine and lysine residues showed a direct association with increased LDL uptake (Spielmann et al., 2009), while sequences with aromatic residues were linked to enhanced antioxidant responses (Monteiro and Paiva-Martins, 2022). These findings suggest a clear structure–activity relationship, where amino acid composition and peptide size strongly dictate biological potency. Such evidence suggests that olive peptides may combine lipid-lowering and antioxidant properties in a multifunctional manner, comparable to but mechanistically distinct from lupin and soy peptides.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Transport of AH and PH through differentiated Caco-2 cell monolayers. Representation of small peptide distribution in the apical (AP) and basolateral (BL) compartments for AH (a) and PH (b), with peptide sequences shown on the x-axis and signal intensity on the y-axis. Adapted from (Bartolomei et al., 2024). |

| 4. Mechanistic insights of olive bioactives | ▴Top |

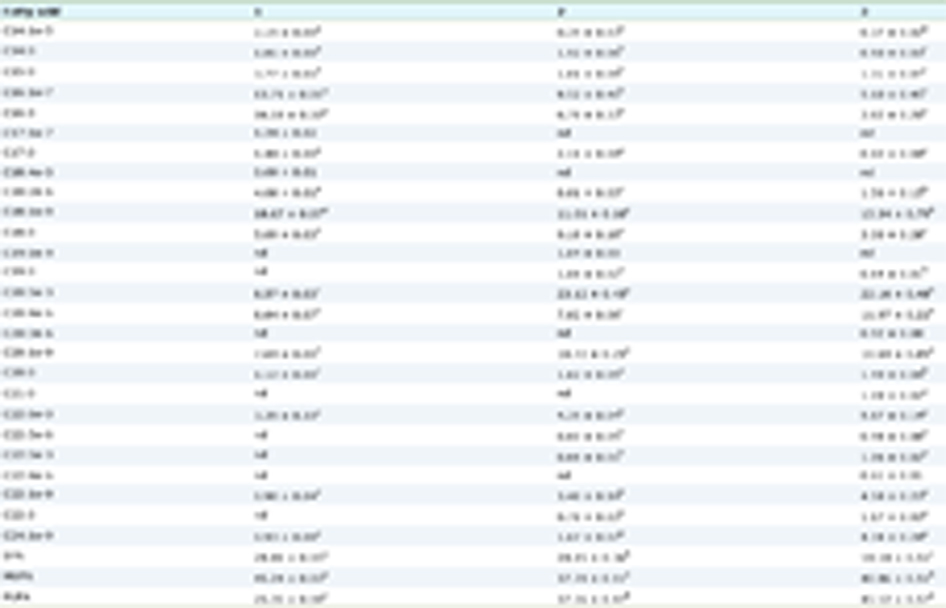

Computational and molecular docking studies provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the bioactivities of olive-derived compounds. Polyphenols such as oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol have been shown to interact with the active sites of COX enzymes, DPP-IV, and antioxidant enzymes, explaining their anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic effects (Corona et al., 2007; Lammi et al., 2021; Napolitano et al., 2010). Olive seed peptides display strong binding affinities toward HMG-CoA reductase and PCSK9, rationalizing their lipid-lowering potential. These in silico findings corroborate experimental evidence and highlight the synergistic effects of complex mixtures (Bartolomei et al., 2024). In addition to docking studies, molecular dynamics simulations have confirmed the stability of interactions between olive-derived peptides and HMG-CoA reductase, suggesting a sustained inhibitory effect over time (Alsenani et al., 2025). Structural modeling further indicates that specific peptide sequences engage in hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with catalytic residues, reinforcing their lipid-lowering efficacy (Prados et al., 2020). Polyphenols such as hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein metabolites also display strong binding affinities for COX-2 and DPP-IV, supporting their anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic properties even after metabolic transformation (Frumuzachi et al., 2024; Lammi et al., 2021). At the cellular level, olive hydrolysates in HepG2 hepatocytes have been shown to downregulate intracellular cholesterol synthesis while increasing LDL uptake, consistent with in silico predictions (Bartolomei et al., 2024; Prados et al., 2020). In endothelial cells, oleuropein enhances nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, thereby improving vascular reactivity and reducing oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction (Summerhill et al., 2018). Recent omics-based studies, including transcriptomics and proteomics, have revealed modulation of key pathways involved in lipid metabolism, oxidative stress responses, and inflammation, providing system-level confirmation of the multi-target mode of action (Garcia-Segura et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2025). Taken together, these insights emphasize that olive-derived polyphenols and peptides do not act through a single mechanism but rather through a network of molecular interactions that exert synergistic benefits for metabolic health (Garrido-Romero et al., 2025). In addition to lipid-lowering effects, olive-derived peptides exert strong antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by their capacity to reduce intracellular ROS levels, protect against lipid peroxidation, and preserve mitochondrial membrane potential (Bartolomei et al., 2022). These antioxidant effects are tightly linked to their amino acid composition, with hydrophobic and aromatic residues (such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan) contributing to radical scavenging capacity, while positively charged residues (arginine, lysine) enhance interactions with negatively charged radical species (Nwachukwu and Aluko, 2019). Structure–activity relationship (SAR) analyses have revealed that shorter peptides, typically di- and tripeptides, exhibit higher transport efficiency across the intestinal barrier and retain strong bioactivities once internalized (Karaś, 2019). Peptidomic profiling of olive seed hydrolysates identified several low-molecular-weight sequences with potential multifunctionality, including fragments rich in proline and valine that are associated with hypocholesterolemic actions, and sequences containing aromatic residues that correlate with antioxidant capacity (Bartolomei et al., 2024). The dual presence of these motifs within single peptides highlights a unique feature of olive-derived sequences: their ability to simultaneously modulate lipid metabolism and oxidative stress. Correlation analyses between peptidomic fingerprints and biological assays have confirmed that fractions enriched in smaller peptides display the highest biological potency, underscoring the central role of peptidomics in guiding the discovery and optimization of novel nutraceutical peptides. Numerical activity spans reported in the literature vary widely depending on sequence and assay conditions. Across curated datasets, di-/tripeptide DPP-IV IC50 values typically fall within the tens-to-low-thousands μM range, with Pro-containing and N-terminal hydrophobic/aromatic motifs clustering at the more potent end of the spectrum (Mu et al., 2024). For HMG-CoA reductase, short food-derived peptides frequently exhibit micromolar-to-sub-millimolar inhibition in cell-free assays, with lipid-lowering corroborated in cell and animal models (Sánchez et al., 2024). Antioxidant potency for short peptides scales with aromatic content and is often confirmed across ORAC/DPPH and cellular ROS assays (Zhao and Liu, 2023). Recent studies have refined the structure–activity relationships (SAR) governing small bioactive peptides (Table 5). For DPP-IV inhibition, quantitative modeling and mechanistic analyses converge on a few consistent principles: (1) short length (di-/tripeptides, occasionally up to penta) favors both target recognition and transepithelial transport (Wu et al., 2024); (2) hydrophobic and/or aromatic residues at the N-terminus (Leu, Val, Ile, Phe, Trp) improve the DPP-IV hydrophobic pocket binding ; (3) Pro-contained motifs (X–Pro or Pro at positions 2/4 of tri-/pentapeptides) show potent inhibition properties due to the ability of DPP-IV to preferentially recognize this motif as substrate (Wu et al., 2024) . These features agree with the peptidomic profiles observed in olive seed hydrolysates (enrichment in low–molecular-weight, hydrophobic/aromatic and Pro-containing fragments), and for this reason, they can help explain their dual DPP-IV inhibitory and antioxidant activities, respectively(Bartolomei et al., 2022). Moreover, the same hydrophobic/aromatic motifs can also correlate HMGCoAR binding across food-derived peptides, suggesting a unifying physicochemical basis for multifunctionality (glycemic and lipid modulation plus redox buffering) (Prados et al., 2020).

Click to view | Table 5. Small-peptide SAR across sources: DPP-IV, antioxidant, and HMGCoAR links |

| 5. Future perspectives and challenges | ▴Top |

The valorization of olive oil by-products into health-promoting ingredients has significant translational implications. Polyphenol-rich extracts and peptide hydrolysates can be incorporated into functional foods, dietary supplements, and cosmeceuticals. Developing robust quality control protocols and scalable industrial processes will be essential to ensure reproducibility. Indeed, industrial scalability represents an important challenge, and it requires a deep industrial optimization and set up of hydrolytic process and purification step for obtaining large scale fractions enriched in medium- and short- chain peptides which are correlated to the biological activity. The industrial production should be robust and reproducible for guarantee the same peptidomic profile every round of industrial production. In addition, it is important to overcame critical issue related to the by-products variability, which depends on olive cultivar, geographical origin, agronomic practices, and production processes. EFSA has approved health claims for olive polyphenols, while peptides are likely to require novel food authorization, presenting both challenges and opportunities for innovation. For this reason, in the regulatory framework, clinical study must be performed to validate olive derive peptides’ health promoting activity in term of efficacy and safety. Strategies to improve bioavailability, such as encapsulation, nanoformulation, or co-administration with other bioactives, will be critical. Moreover, AI-driven approaches to peptide discovery and peptidomics can accelerate the identification of potent sequences. Integration of olive by-product valorization into the bioeconomy also supports the European Green Deal, ensuring that scientific innovation contributes to both health and sustainability goals. Long-term randomized clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm the efficacy of both polyphenols and peptides in reducing cardiovascular and metabolic risk in diverse populations. Such studies should also evaluate dose-response relationships, optimal delivery formats (capsules, functional foods, or beverages), and potential synergistic interactions between polyphenols, peptides, and other dietary components.

| 6. Conclusions | ▴Top |

Olive oil co- and/or by-products represent valuable sources of polyphenols and peptides displaying multifunctional properties, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypocholesterolemic, and antidiabetic ones. Among the various bioactive constituents identified in these matrices, polyphenols and bioactive peptides have emerged as particularly promising due to their broad spectrum of biological effects and relevance to human health. Polyphenols in extra virgin olive oil are strongly influenced by genetic and environmental factors, such as cultivar, climate, and processing, which in turn determine their phenolic profile and the oil’s potential to meet the EFSA threshold for the health claim. Likewise, the olive genotype and origin play a key role in shaping the bioactivity of olive seeds peptides, as demonstrated by studies showing varietal differences in lipid-lowering effects and the influence of processing enzymes on functional outcomes. Moreover, scaling up production requires robust hydrolysis and purification methods, while addressing variability in raw materials, and regulatory approvals along with clinical validation are essential to confirm health effects. Strategies to enhance bioavailability, AI-driven peptide discovery, and integration into the circular bioeconomy offer opportunities for innovation, so that in the future they can be considered potential ingredients for the development of nutraceutical and functional foods. In the future, it is crucial to pursue efforts for demonstrating their clinical efficacy and safety for the real implementation on the market of these innovative ingredients.

| References | ▴Top |